How to nurture a love that “would stand as a firm wall,” that “won’t let you fall, and it gives warmth.”

BY MARIA POPOVA

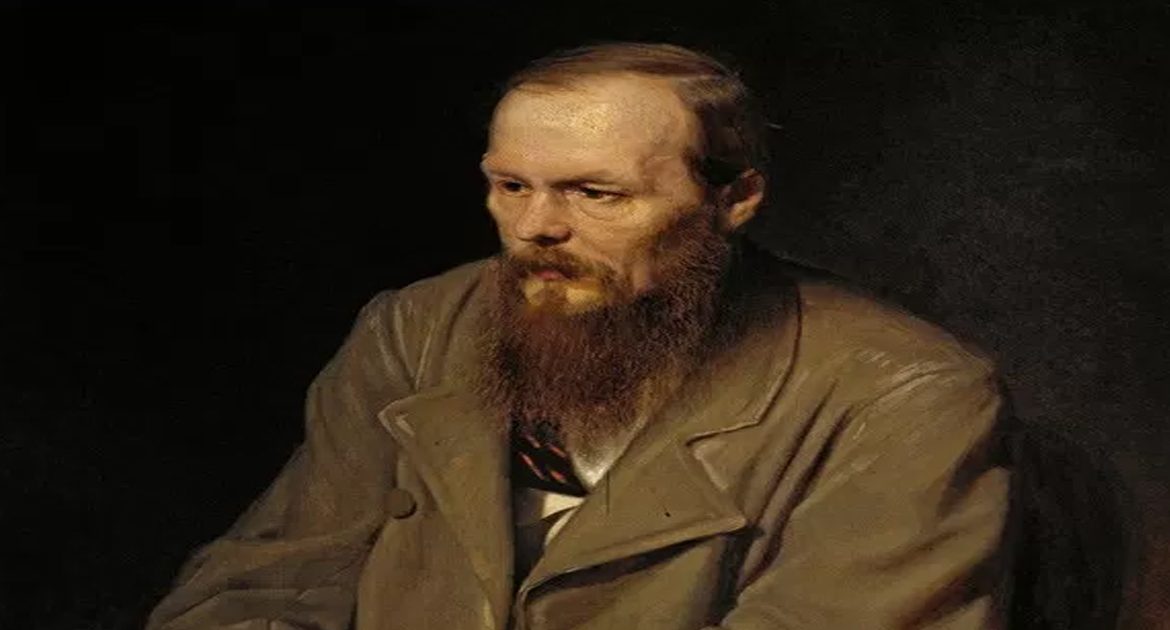

In the summer of 1865, just after he began writing Crime and Punishment, the greatest novelist of all time hit rock bottom. Recently widowed and bedeviled by epilepsy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky (November 11, 1821–February 9, 1881) had cornered himself into an impossible situation. After his elder brother died, Dostoyevsky, already deeply in debt on account of his gambling addiction, had taken upon himself the debts of his brother’s magazine. Creditors soon came knocking on his door, threatening to send him to debtors’ prison. (A decade earlier, he had narrowly escaped the death penalty for reading banned books and was instead exiled, sentenced to four years at a Siberian labor camp — so the prospect of being imprisoned was unbearably terrifying to him.) In a fit of despair, he agreed to sell the rights to an edition of his collected works to his publisher, a man named Fyodor Stellovsky, for the sum of his debt — 3,000 rubles, or around $80,000 in today’s money. As part of the deal, he would also have to produce a new novel of at least 175 pages by November 13 of the following year. If he failed to meet the deadline, he would lose all rights to his work, which would be transferred to Stellovsky for perpetuity.

Only after signing the contract did Dostoyevsky find out that it was his publisher, a cunning exploiter who often took advantage of artists down on their luck, who had purchased the promissory notes of his brother’s debt for next to nothing, using two intermediaries to bully Dostoyevsky into paying the full amount. Enraged but without recourse, he set out to fulfill his contract. But he was so consumed with finishing Crime and Punishment that he spent most of 1866 working on it instead of writing The Gambler, the novel he had promised Stellovsky. When October rolled around, Dostoyevsky languished at the prospect of writing an entire novel in four weeks.

His friends, concerned for his well-being, proposed a sort of crowdsourcing scheme — Dostoyevsky would come up with a plot, they would each write a portion of the story, and he would then only have to smooth over the final product. But, a resolute idealist even at his lowest low, Dostoyevsky thought it dishonorable to put his name on someone else’s work and refused.

There was only one thing to do — write the novel, and write it fast.

On October 15, he called up a friend who taught stenography, seeking to hire his best pupil. Without hesitation, the professor recommended a young woman named Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina. (Stenography, in that era, was a radical innovation and its mastery was so technically demanding that of the 150 students who had enrolled in Anna’s program, 125 had dropped out within a month.)

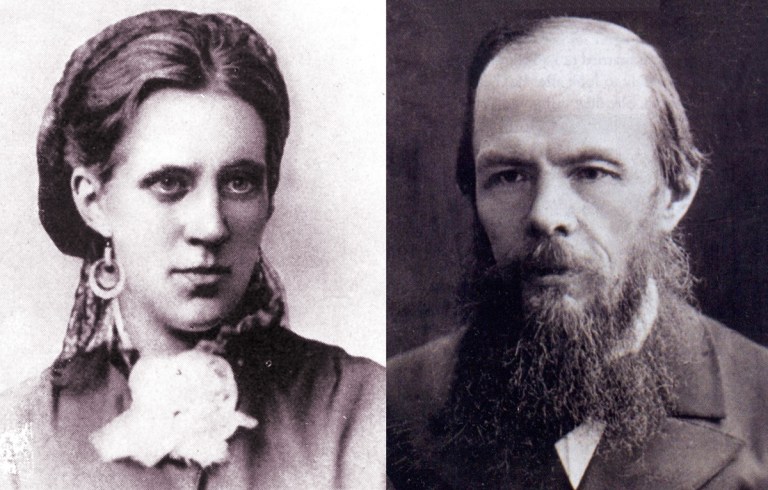

Twenty-year-old Anna, who had taken up stenography shortly after graduating from high school hoping to become financially independent by her own labor, was thrilled by the offer — Dostoyevsky was her recently deceased father’s favorite author, and she had grown up reading his tales. The thought of not only meeting him but helping him with his work filled her with joy.

The following day, she presented herself at Dostoyevsky’s house at eleven-thirty, “no earlier and no later,” as Dostoyevsky had instructed — a favorite expression of his, bespeaking his stringency. Distracted and irritable, he asked her a series of questions about her training. Although she answered each of them seriously and almost dryly, so as to appear maximally businesslike, he somehow softened over the course of the conversation. By the early afternoon, they had begun their collaboration on the novel — he, dictating; she, writing in stenographic shorthand, then transcribing at home at night.

For the next twenty-five days, Anna came to Dostoyevsky’s house at noon and stayed until four. Their dictating sessions were punctuated by short breaks for tea and conversation. With each day, he grew kinder and warmer toward her, and eventually came to address her by his favorite term of endearment, “golubchik” — Russian for “little dove.” He cherished her seriousness, her extraordinary powers of sympathy, how her luminous spirit dissipated even his darkest moods and lifted him out of his obsessive thoughts. She was touched by his kindness, his respect for her, how he took a genuine interest in her opinions and treated her like a collaborator rather than hired help. But neither of them was aware that this deep mutual affection and appreciation was the seed of a legendary love.

In her altogether spectacular memoir of marriage, Dostoevsky Reminiscences (public library), Anna recounts a prescient exchange that took place during one of their tea breaks:

Each day, chatting with me like a friend, he would lay bare some unhappy scene from his past. I could not help being deeply touched at his accounts of the difficulties from which he had never extricated himself, and indeed could not.

[…]

Fyodor Mikhailovich always spoke about his financial straits with great good nature. His stories, however, were so mournful that on one occasion I couldn’t restrain myself from asking, “Why is it, Fyodor Mikhailovich, that you remember only the unhappy times? Tell me instead about how you were happy.”

“Happy? But I haven’t had any happiness yet. At least, not the kind of happiness I always dreamed of. I am still waiting for it.”

Little did either of them know that he was in the presence of that happiness at that very moment. In fact, Anna, in her characteristic impulse for dispelling the darkness with light, advised him to marry again and seek happiness in family. She recounts the conversation:

“So you think I can marry again?” he asked. “That someone might consent to become my wife? What kind of wife shall I choose then — an intelligent one or a kind one?”

“An intelligent one, of course.”

“Well, no… if I have the choice, I’ll pick a kind one, so that she’ll take pity on me and love me.”

While we were on the theme of marriage, he asked me why I didn’t marry myself. I answered that I had two suitors, both splendid people and that I respected them both very much but did not love them — and that I wanted to marry for love.

“For love, without fail,” he seconded me heartily. “Respect alone isn’t enough for a happy marriage!”

Their last dictation took place on November 10. With Anna’s instrumental help, Dostoyevsky had accomplished the miraculous — he had finished an entire novel in twenty-six days. He shook her hand, paid her the 50 rubles they had agreed on — about $1,500 in today’s money — and thanked her warmly.

The following day, Dostoyevsky’s forty-fifth birthday, he decided to mark the dual occasion by giving a celebratory dinner at a restaurant. He invited Anna. She had never dined at a restaurant and was so nervous that she almost didn’t go — but she did, and Dostoyevsky spent the evening showering her with kindnesses.

But when the elation of the accomplishment wore off, he suddenly realized that his collaboration with Anna had become the light of his life and was devastated by the prospect of never seeing her again. Anna, too, found herself sullen and joyless, her typical buoyancy weighed down by an acute absence. She recounts:

I had grown so accustomed to that merry rush to work, the joyful meetings and the lively conversations with Dostoyevsky, that they had become a necessity to me. All my old activities had lost their interest and seemed empty and futile.

Unable to imagine his life without her, Dostoyevsky asked Anna if she would help him finish Crime and Punishment. On November 20, exactly ten days after the end of their first project, he invited her to his house and greeted her in an unusually excited state. They walked to his study, where he proceeded to propose marriage in the most wonderful and touching way.

Dostoyevsky told Anna that he would like her opinion on a new novel he was writing. But as soon as he began telling her the plot, it became apparent that his protagonist was a very thinly veiled version of himself, or rather of him as he saw himself — a troubled artist of the same age as he, having survived a harsh childhood and many losses, plagued by an incurable disease, a man “gloomy, suspicious; possessed of a tender heart … but incapable of expressing his feelings; an artist and a talented one, perhaps, but a failure who had not once in his life succeeded in embodying his ideas in the forms he dreamed of, and who never ceased to torment himself over that fact.” But the protagonist’s greatest torment was that he had fallen desperately in love with a young woman — a character named Anya, removed from reality by a single letter — of whom he felt unworthy; a gentle, gracious, wise, and vivacious girl whom he feared he had nothing to offer.

Only then did it dawn on Anna that Dostoyevsky had fallen in love with her and that he was so terrified of her rejection that he had to feel out her receptivity from behind the guise of fiction.

Is it plausible, Dostoyevsky asked her, that the alleged novel’s heroine would fall in love with its flawed hero? She recounts the words of literature’s greatest psychological writer:

“What could this elderly, sick, debt-ridden man give a young, alive, exuberant girl? Wouldn’t her love for him involve a terrible sacrifice on her part? And afterwards, wouldn’t she bitterly regret uniting her life with his? And in general, would it be possible for a young girl so different in age and personality to fall in love with my artist? Wouldn’t that be psychologically false? That is what I wanted to ask your opinion about, Anna Grigoryevna.”

“But why would it be impossible? For if, as you say, your Anya isn’t merely an empty flirt and has a kind, responsive heart, why couldn’t she fall in love with your artist? What if he is poor and sick? Where’s the sacrifice on her part, anyway? If she really loves him, she’ll be happy, too, and she’ll never have to regret anything!”

I spoke with some heat. Fyodor Mikhailovich looked at me in excitement. “And you seriously believe she could love him genuinely, and for the rest of her life?”

He fell silent, as if hesitating. “Put yourself in her place for a moment,” he said in a trembling voice. “Imagine that this artist — is me; that I have confessed my love to you and asked you to be my wife. Tell me, what would you answer?”

His face revealed such deep embarrassment, such inner torment, that I understood at long last that this was not a conversation about literature; that if I gave him an evasive answer I would deal a deathblow to his self-esteem and pride. I looked at his troubled face, which had become so dear to me, and said, “I would answer that I love you and will love you all my life.”

I won’t try to convey the words full of tenderness and love that he said to me then; they are sacred to me. I was stunned, almost crushed by the immensity of my happiness and for a long time I couldn’t believe it.

Fyodor and Anna were married on February 15, 1867, and remained besotted with one another until Dostoyevsky’s death fourteen years later. Although they suffered financial hardship and tremendous tragedy, including the death of two of their children, they buoyed each other with love. Anna took it upon herself to lift the family out of debt by making her husband Russia’s first self-published author. She studied the book market meticulously, researched vendors, masterminded distribution plans, and turned Dostoyevsky into a national brand. Today, many consider her Russia’s first true businesswoman. But beneath her business acumen was the same tender, enormous heart that had made loving room within itself for a brilliant man with all of his demons.

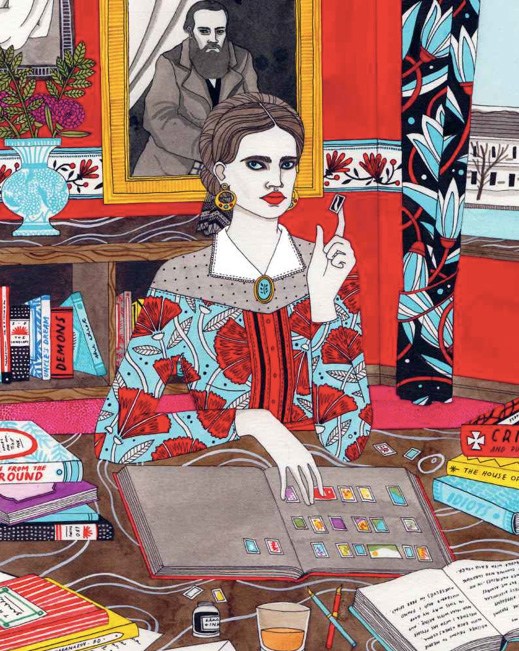

Anna Dostoyevskaya by Laura Callaghan from The Who, the What, and the When

In the afterword to her memoir, Anna reflects on the secret to their deep and true marriage — one of the greatest loves in the history of creative culture:

Throughout my life it has always seemed a kind of mystery to me that my good husband not only loved and respected me as many husbands love and respect their wives, but almost worshipped me, as though I were some special being created just for him. And this was true not only at the beginning of our marriage but through all the remaining years of it, up to his very death. Whereas in reality I was not distinguished for my good looks, nor did I possess talent nor any special intellectual cultivation, and I had no more than a secondary education. And yet, despite all that, I earned the profound respect, almost the adoration of a man so creative and brilliant.

This enigma was cleared up for me somewhat when I read V.V. Rozanov’s note to a letter of Strakhov dated January 5, 1890, in his book Literary Exiles. Let me quote:

“No one, not even a ‘friend,’ can make us better. But it is a great happiness in life to meet a person of quite different construction, different bent, completely dissimilar views who, while always remaining himself and in no wise echoing us nor currying favor with us (as sometimes happens) and not trying to insinuate his soul (and an insincere soul at that!) into our psyche, into our muddle, into our tangle, would stand as a firm wall, as a check to our follies and our irrationalities, which every human being has. Friendship lies in contradiction and not in agreement! Verily, God granted me Strakhov as a teacher and my friendship with him, my feelings for him were ever a kind of firm wall on which I felt I could always lean, or rather rest. And it won’t let you fall, and it gives warmth.”

In truth, my husband and I were persons of “quite different construction, different bent, completely dissimilar views.” But we always remained ourselves, in no way echoing nor currying favor with one another, neither of us trying to meddle with the other’s soul, neither I with his psyche nor he with mine. And in this way my good husband and I, both of us, felt ourselves free in spirit.

Fyodor Mikhailovich, who reflected so much in so much solitude on the deepest problems of the human heart, doubtless prized my non-interference in his spiritual and intellectual life. And therefore he would sometimes say to me, “You are the only woman who ever understood me!” (That was what he valued above all.) He looked on me as a rock on which he felt he could lean, or rather rest. “And it won’t let you fall, and it gives warmth.”

It is this, I believe, which explains the astonishing trust my husband had in me and in all my acts, although nothing I ever did transcended the limits of the ordinary. It was these mutual attitudes which enabled both of us to live in the fourteen years of our married life in the greatest happiness possible for human beings on earth.

Complement the wholly enchanting Dostoevsky Reminiscences with Frida Kahlo’s touching remembrance of Diego Rivera, Jane Austen’s advice on love and marriage, and philosopher Erich Fromm on what is keeping us from mastering the art of loving, then revisit Dostoyevsky on why there are no bad people and the day he discovered the meaning of life in a dream.