History has a funny way of repeating itself, especially when the people repeating it aren’t exactly telling the full story. Indeed, many of the clean, easy, wholesome «facts» you learned in history class would earn you a big fat F in the decades-long class that is Real Life. Here are a few historical lies that will make you rethink your entire education:

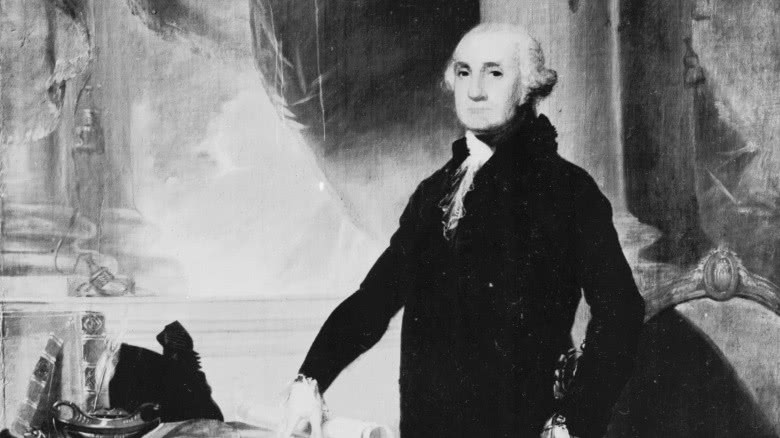

George Washington didn’t chop down his dad’s cherry tree

For decades, it seemed like every American classroom couldn’t get through the Revolutionary War without teaching the story about how America’s first president, George Washington, famously confessed to chopping down his father’s cherry tree when he was just six years old. «I cannot tell a lie,» allegedly said little G. W. Well, as it turns out, that story was itself a lie. Oh, the irony. The story has become such an infamous myth over the years that even the official website of the home of Washington, Mount Vernon, has squashed it once and for all, claiming the whole thing was made up by Washington biographer Mason Locke Weems in 1806. Among his alleged reasons for lying, according to the website: profits, the desire to look at Washington’s private life, and the need to «present Washington as the perfect role model, especially for young Americans.» Whatever the reason, the myth worked for centuries.

For decades, it seemed like every American classroom couldn’t get through the Revolutionary War without teaching the story about how America’s first president, George Washington, famously confessed to chopping down his father’s cherry tree when he was just six years old. «I cannot tell a lie,» allegedly said little G. W. Well, as it turns out, that story was itself a lie. Oh, the irony. The story has become such an infamous myth over the years that even the official website of the home of Washington, Mount Vernon, has squashed it once and for all, claiming the whole thing was made up by Washington biographer Mason Locke Weems in 1806. Among his alleged reasons for lying, according to the website: profits, the desire to look at Washington’s private life, and the need to «present Washington as the perfect role model, especially for young Americans.» Whatever the reason, the myth worked for centuries.

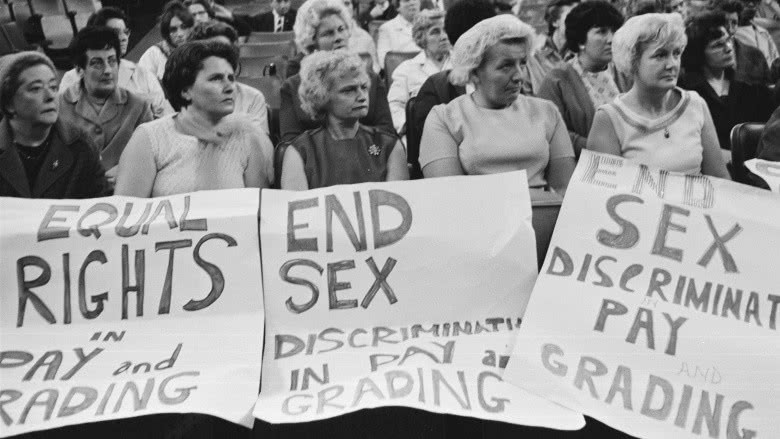

The Feminist movement didn’t involve bra-burning

When classrooms gloss through the Women’s Liberation Movement, one of the topics that almost always gets brought up is the Movement’s protest of the 1968 Miss America pageant, in Atlantic City, New Jersey. According to history, we were told that a bunch of protesters at the event took off their bras and immediately set fire to them. Well, according to Carol Hanisch, one of the organizers of the protest, that’s not exactly what went down. Truth be told: the women did want to burn their bras; Hanisch admitted that much to NPR in an interview 30 years after the protest took place. But because police wouldn’t let them do that on a boardwalk, they were forced to throw a bunch of «instruments of female torture» like bras, girdles and Playboy magazines into a garbage can. It was inside that garbage in which the fire was ultimately lit. «The media picked up on the bra part,» Hanisch told NPR, dispelling the «bra-burning» myth once and for all. «I often say that if they had called us ‘girdle burners,’ every woman in America would have run to join us.»

When classrooms gloss through the Women’s Liberation Movement, one of the topics that almost always gets brought up is the Movement’s protest of the 1968 Miss America pageant, in Atlantic City, New Jersey. According to history, we were told that a bunch of protesters at the event took off their bras and immediately set fire to them. Well, according to Carol Hanisch, one of the organizers of the protest, that’s not exactly what went down. Truth be told: the women did want to burn their bras; Hanisch admitted that much to NPR in an interview 30 years after the protest took place. But because police wouldn’t let them do that on a boardwalk, they were forced to throw a bunch of «instruments of female torture» like bras, girdles and Playboy magazines into a garbage can. It was inside that garbage in which the fire was ultimately lit. «The media picked up on the bra part,» Hanisch told NPR, dispelling the «bra-burning» myth once and for all. «I often say that if they had called us ‘girdle burners,’ every woman in America would have run to join us.»

Paul Revere didn’t yell «The British are coming!»

If your dusty old history books are to be believed, the build-up to the American Revolutionary War was pretty dramatic: a dude named Paul Revere rode through a bunch of towns on horseback screaming «The British are coming!» and everyone freaked out and got their guns and the war started the next day. As it turns out, that only sort-of happened. Revere was indeed ordered to Lexington, Massachusetts, to tell Samuel Adams and John Hancock that the British were coming. But the actual quote has since been misconstrued. According to the website for The Paul Revere House, a sentry at the house where Adams and Hancock were staying got all mad at Revere when he arrived because he was making too much noise. To which Revere replied dramatically: «Noise! You’ll have noise long enough before. The regulars are coming out!» Sure, that may sound less like a movie moment and more like a bad regional theater production, but hey, facts are facts. And speaking of: the website goes on to say that Revere was joined by two additional riders, all of whom were arrested and released on their way to Concord. No word on whether they, too, had a catch phrase.

If your dusty old history books are to be believed, the build-up to the American Revolutionary War was pretty dramatic: a dude named Paul Revere rode through a bunch of towns on horseback screaming «The British are coming!» and everyone freaked out and got their guns and the war started the next day. As it turns out, that only sort-of happened. Revere was indeed ordered to Lexington, Massachusetts, to tell Samuel Adams and John Hancock that the British were coming. But the actual quote has since been misconstrued. According to the website for The Paul Revere House, a sentry at the house where Adams and Hancock were staying got all mad at Revere when he arrived because he was making too much noise. To which Revere replied dramatically: «Noise! You’ll have noise long enough before. The regulars are coming out!» Sure, that may sound less like a movie moment and more like a bad regional theater production, but hey, facts are facts. And speaking of: the website goes on to say that Revere was joined by two additional riders, all of whom were arrested and released on their way to Concord. No word on whether they, too, had a catch phrase.

Napoleon reportedly wasn’t that short

One of the best—okay, funniest—parts about studying the French Revolution in social studies class was finding out that the famous French military leader, Napoleon Bonaparte, was actually super-short in height. Just how short, you ask? Well, according to teachers all over the country, Napoleon stood a measly 5’2″. Granted, his alleged height didn’t stop him from kicking ass during the war; however, it did become infamous enough to create the term the «Napoleon complex,» used to describe people who make up for their short height by being totally strong and aggressive, socially. In any case, despite all of this, Napoleon’s height has since been up for debate. According to the BBC, historians are now estimating that he was actually more along the lines of 5’6″—or, more to the point, one inch taller than former President of France Nicolas Sarkozy. What happened? The BBC claims the height might have gotten lost in translation between French and British measurements. Which, if you really think about it, is a Napoleon complex in of itself.

One of the best—okay, funniest—parts about studying the French Revolution in social studies class was finding out that the famous French military leader, Napoleon Bonaparte, was actually super-short in height. Just how short, you ask? Well, according to teachers all over the country, Napoleon stood a measly 5’2″. Granted, his alleged height didn’t stop him from kicking ass during the war; however, it did become infamous enough to create the term the «Napoleon complex,» used to describe people who make up for their short height by being totally strong and aggressive, socially. In any case, despite all of this, Napoleon’s height has since been up for debate. According to the BBC, historians are now estimating that he was actually more along the lines of 5’6″—or, more to the point, one inch taller than former President of France Nicolas Sarkozy. What happened? The BBC claims the height might have gotten lost in translation between French and British measurements. Which, if you really think about it, is a Napoleon complex in of itself.

An apple didn’t fall on Issac Newton’s head

When the history of Isaac Newton is taught, many teachers quote the old story that the physicist and mathematician actually came up with his theory for gravity after an apple fell from a tree he was sitting under and hit him smack on the head. You probably believed it in part because, duh, it’s an old story and, duh, Newton was really smart. But, again, this story is only sort-of true. While Newton did actually put two and two together by watching an apple fall, The Royal Society in London concluded in 2010 that the incident took place in his mother’s garden and that there is «there is no evidence to suggest that it hit him on the head.» That’s a bit of a bummer. But, hey, he still came up with the theory of gravity, which is more than anyone reading this article can probably say.

When the history of Isaac Newton is taught, many teachers quote the old story that the physicist and mathematician actually came up with his theory for gravity after an apple fell from a tree he was sitting under and hit him smack on the head. You probably believed it in part because, duh, it’s an old story and, duh, Newton was really smart. But, again, this story is only sort-of true. While Newton did actually put two and two together by watching an apple fall, The Royal Society in London concluded in 2010 that the incident took place in his mother’s garden and that there is «there is no evidence to suggest that it hit him on the head.» That’s a bit of a bummer. But, hey, he still came up with the theory of gravity, which is more than anyone reading this article can probably say.

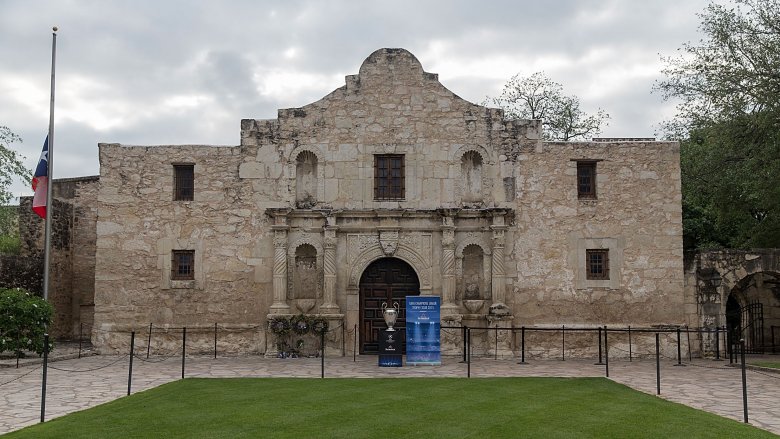

The Alamo was Mexican villains versus American heroes

The battle at the Alamo is usually taught as a bunch of heroic white Americans fighting for freedom against the dastardly Mexicans. You picture John Wayne standing stoically, a perfect American hero brave enough to fight to the death. Sadly, that barely resembles what happened.

The battle at the Alamo is usually taught as a bunch of heroic white Americans fighting for freedom against the dastardly Mexicans. You picture John Wayne standing stoically, a perfect American hero brave enough to fight to the death. Sadly, that barely resembles what happened.

When Mexico gained independence in 1821, they weren’t sure what to do with Texas. Eventually, they offered the land to Americans to live cheaply and tax-free for seven years as long as they swore allegiance to Mexico and became Catholic. So, pick up a rosary and get a big Texas ranch? A lot of Americans took them up on the offer.

Mexico was so eager to settle Texas, they even let landowners keep slaves. Slavery had been abolished in Mexico for years, but they were willing to bend the rules for slave-loving white guys. By 1830, Americans outnumbered Mexicans in the Texas area five to one. President Santa Anna issued a stop on immigration from the US, but those pesky American illegal immigrants kept pouring in. By 1834, Mexico started getting rid of illegal aliens. Since it seemed heartless and rude to remove peaceful immigrants who simply wanted a better life in Mexico, Texas got ready to fight for independence.

At one point, David Crockett, James Bowie, and William Travis got to the Alamo, a decaying fortress the Texans had seized from Mexico, to join the fight for freedom. Here’s where things divert from history class. These three men weren’t ideal heroes. Bowie was a slave smuggler and con man, though he got along well with the Tejano community of the state. Travis was a lawyer who didn’t care for the Mexican people who lived in the Mexican territory. Crockett was the closest to his fictional counterpart. A very popular military man who served in Congress, Crockett was a charming celebrity of the age. Still, it’s unlikely he killed him a «bar» when he was only three.

When the battle of the Alamo commenced, it was far from a war of white versus brown. Tejanos, Americans, native Mexican Indians who spoke no Spanish, and slaves all fought for the side of Texas. Santa Anna was brutal, and in the end, most of the American soldiers fought to their death. Santa Anna burned their bodies in a heap in front of the destroyed mission as a lesson to future rebels.

Texans spread the word of the Alamo and greatly exaggerated the tale. When the rebels and Santa Anna’s men fought again, the Texan soldiers killed any Mexicans they could find, whether they were soldiers or not. The Smithsonian Magazine wrote that a young Mexican drummer boy asked for his life and died for the request. The slaughter in the name of the Alamo was just as bad as the battle of the Alamo itself, if not much worse. And the efforts of all the brave Tejanos, slaves, Indians, and all the other non-white people were completely erased from history.

Bastille Day celebrates releasing political prisoners and starting the French Revolution

While you’re busy relaxing on a beach somewhere or nursing a hangover from a really epic Fourth of July party, you might notice somebody’ll post about France on July 14. That’s Bastille Day, a day of French Independence to mark the famous storming of the Bastille to free the unjustly imprisoned and start the revolution. Or so you think.

While you’re busy relaxing on a beach somewhere or nursing a hangover from a really epic Fourth of July party, you might notice somebody’ll post about France on July 14. That’s Bastille Day, a day of French Independence to mark the famous storming of the Bastille to free the unjustly imprisoned and start the revolution. Or so you think.

After King Louis XVI dragged the nation into poverty then tried to drastically raise taxes to cover his behind, the people of France weren’t thrilled with his leadership. On July 14, 1789, the French had had enough and went on a quest to find guns and ammo to start fighting back. The Bastille was once full of political prisoners, but by 1789, the place was nearly empty with just a handful of prisoners left inside. When revolutionaries came to the Bastille doors, they weren’t there to free prisoners. They showed up to get more gunpowder.

Since the freedom fighters were all riled up, their powder raid turned violent, and they killed and beheaded the prison officers while freeing the remaining jailmates. So, the raid of the Bastille was really just a looting gone wrong. But it scared the crap out of the king, who agreed to compromise with the rebellion and end feudalism. Since the Bastille raid came at the right time, it turned from a tale about stealing gunpowder and going beheading happy into a tale of a fight against tyranny. So, when you’re celebrating Bastille Day with your traditional baguette and inflated sense of superiority to honor France, remember you’re really honoring a bunch of jerks who cut off some heads for pretty much no reason.

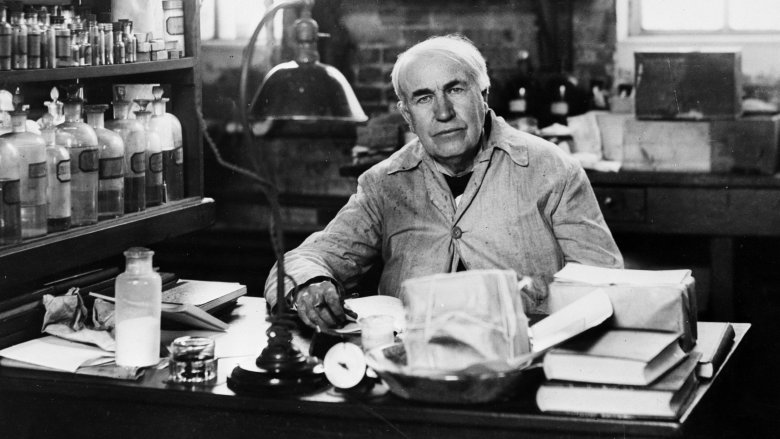

Edison was a great inventor

In school, we learn that Thomas Edison was a great inventor who gave America the gift of light in bulb form. You can’t deny that Edison was a bright mind who developed several things that made life easier for everybody. But you should also learn that Edison was a monopolizing, thieving jerk.

In school, we learn that Thomas Edison was a great inventor who gave America the gift of light in bulb form. You can’t deny that Edison was a bright mind who developed several things that made life easier for everybody. But you should also learn that Edison was a monopolizing, thieving jerk.

Firstly, he didn’t really invent the lightbulb. He built upon several other inventions, and some say he stole several innovations that led him to creating and taking credit for the bulb we know today. Edison gets sole credit because he was great at telling people he invented the lightbulb and getting publicity. And the bulb is just one of the questionable inventions of Edison’s career.

Edison had a team of workers at his Menlo Park, New Jersey, facility, and in 1892, they invented the kinescope. It was the beginning of moving pictures, where you could pay a nickel to see grainy footage of a girl dancing for six seconds. It may not sound entertaining now, but the idea of moving pictures was pretty ingenious. Plus you saw a girl move her hips back, and if you paid another nickel, forth! Edison’s assistants tried to get him to invest more time into inventing a projection device for this new technology, but Edison thought there was no money in moving pictures.

After kinescopes became incredibly popular, Edison did a 180 and started working on a projecting device. Or rather, Edison asked other people who made innovations on projector technology to file the patent in his name, while he gave them a decent one-time fee. People thought that was a morally questionable move, and Edison replied, «Everyone steals in industry and commerce. I’ve stolen a lot myself. The thing is to know how to steal.» Later, Edison tried to monopolize the film industry and forced filmmakers to move to California to avoid his many lawsuits, giving birth to Hollywood.

Lastly, Edison killed an elephant to prove that his crappy electricity was the best. Edison was a proponent of direct current (DC) electricity, while Nikola Tesla touted alternating current (AC) as the best option. AC enabled long-distance power transmission and is now used exclusively in every home (though some technology like computers use both). But Edison didn’t have the patents for AC, so he went on a major campaign to prove the dangers of alternating current. His biggest stunt was electrocuting Topsy the elephant to prove that AC currents were so dangerous, it could kill the giant creature. Then, to be even more of a jerk, Edison filmed the event and released Electrocuting an Elephant to theaters. The video is available on YouTube, but we won’t link to it here. We’re not as gross as Edison.

Gandhi was nearly a saint

Picking on Gandhi seems like a pretty low blow or a decent name for an emo band. So, awful, either way.

Picking on Gandhi seems like a pretty low blow or a decent name for an emo band. So, awful, either way.

The idea that the mind behind the non-violent fight for India’s independence could be anything less than pure seems almost heretical. In fact, Pulitzer prize–winning journalist Joseph Lelyveld’s realistic biography of Gandhi has been banned in Gandhi’s home state of Gujarat for blasphemy. But that doesn’t make Lelyveld’s words any less true.

Most of us don’t know that Gandhi abandoned his wife to live with a rich male body builder before he got involved in British-Indian relations. Now, if Gandhi was gay, who cares? But Gandhi tried to get all references to homosexual traditions erased from Indian temples in an act he called «sexual cleansing.» And to test his resistance to sexual temptation, he’d sleep in bed naked with his teenage grand-nieces. But worse than his sexual hypocrisy was his terrible racism.

Gandhi may have wanted India freed from British rule, but he was perfectly happy with the rigid caste system of the nation. Gandhi wrote of a time when he and his followers were led to a lower caste jail for protesting. «We could understand not being classed with whites, but to be placed on the same level as the Natives seemed too much to put up with. Kaffirs [the South African equivalent of the N-word] are as a rule uncivilized—the convicts even more so. They’re troublesome, very dirty and live like animals.» When asked about Indian views on race versus white South Africans, he wrote «We believe as much in the purity of races as we think they do.» Though Gandhi did bring some good to the world and was tragically assassinated, we also need to learn that he was only human—and a human with some truly abhorrent ideas.

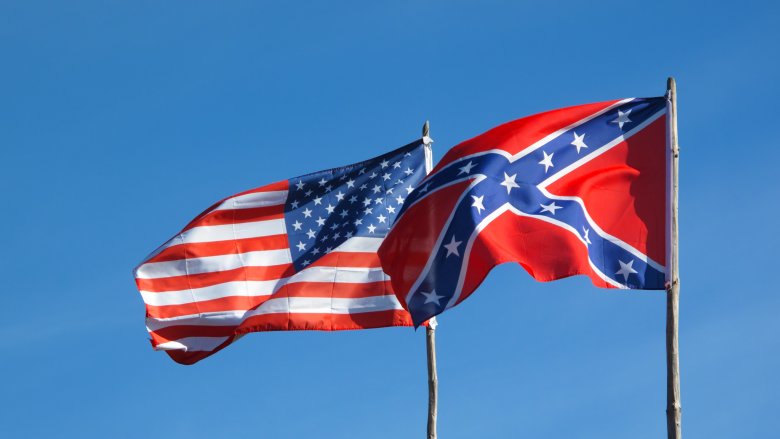

Slavery was just in the South

Though school taught us something different, Southerners didn’t get a patent on racism, and people of the North have a bad history of slavery.

Though school taught us something different, Southerners didn’t get a patent on racism, and people of the North have a bad history of slavery.

The colonial North thrived on the slave trade in the 1700s. During the Revolution, George Washington told Northern and Southern colonists that we must fight the British so we don’t become «as tame and abject slaves as the blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway.» By 1804, slavery was abolished in the North, but not all at once. Some states left in provisions to slowly free slaves over time, and by 1840, Connecticut still had 17 slaves listed on the census.

In New York City, the situation was worse. A fifth of the city’s population were slaves in 1740. Slave labor built the titular wall of Wall Street, Fort Amsterdam, the first city hall, and a lot more. Though they weren’t working on plantations, they were worked mercilessly and treated with as much abuse as any Southern slave.

Even during the Civil War, New York City came close to joining the secession after South Carolina. Though the city wanted to side with the South mostly for economic reasons, they still weren’t worried about the idea of siding with slaveholders. The New York Herald wrote, «If Lincoln is elected, you will have to compete with the labor of four million emancipated negroes.» So, if a Yankee guy gets a little high and mighty around his Southern friends, just remind him of that quote and watch his liberal guilt consume him.

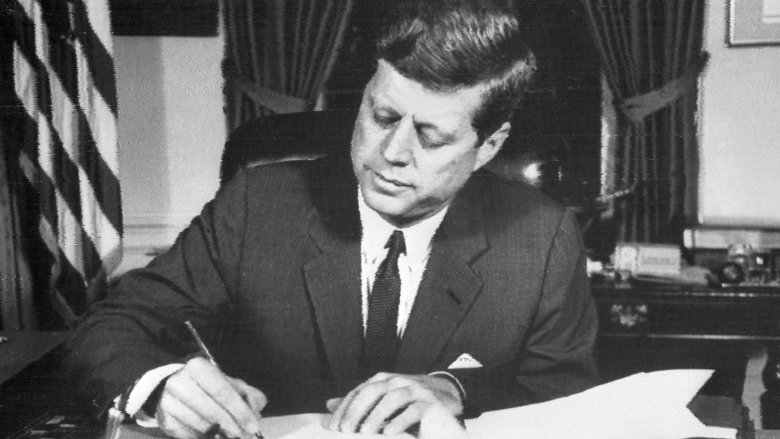

President Kennedy brought about Civil Rights Legislation

Without Kennedy, we may never have had civil rights legislation, or so we’ve been taught. But Kennedy had little to do with civil rights laws. When he heard about the planned March on Washington, where Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his «I Have a Dream» speech, Kennedy tried to stop it. He even sent vice president Lyndon B. Johnson to Norway during the march because he didn’t like LBJ’s pro–civil rights policies.

Without Kennedy, we may never have had civil rights legislation, or so we’ve been taught. But Kennedy had little to do with civil rights laws. When he heard about the planned March on Washington, where Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his «I Have a Dream» speech, Kennedy tried to stop it. He even sent vice president Lyndon B. Johnson to Norway during the march because he didn’t like LBJ’s pro–civil rights policies.

Kennedy was forced to act on civil rights after the Freedom Riders and the assassination of Medgar Evers, but he thought the legislation would never get through and would hurt his chances of passing the bills he really cared about. But after Kennedy was shot, LBJ put all his efforts as president behind the Civil Rights Act. Capitalizing on the fresh memory of the young president slain, LBJ used the people’s grief and frustration to get Congress to act. And in the end, JFK got all the credit.

Women stayed at home and men worked till the Feminist Movement

The minimal women’s history you learn in school usually revolves around the idea that ladies always had to stay at home, then had to go to work in the factories during World War II, but went back home after the war until feminism came along. But this is far from the full picture. Yes, lots of women were housewives or mothers and not allowed or not encouraged to work after getting married. But that ignores the many other women who didn’t have the privilege of not working. Plus, it hides decades of history where men and women worked equally.

Before the Industrial Revolution, work was an extension of the household, and tasks were split evenly between men and women. Even by the turn of the century, women held a quarter of industrial jobs and half of agrarian jobs. Factory work at the time was incredibly dangerous, and gendered labor laws reinforced the growing idea that men should earn the money and women should stay at home. Still, women of color didn’t get that luxury. Even after marriage, many continued to work since their husbands were paid less and had poorer jobs. When white women started to see progress, women of color were usually left out of the conversation.

Even in the ’50s, women workers weren’t so rare. Look magazine often profiled female workers, and radio programs talked to «career girls» who felt women should be able to find meaning and purpose outside the home. Sure, the males on the panel thought she wasn’t serious about having a career because she occasionally thought of falling in love, but we’re not here to debunk the idea that ’50s white guys had issues.

But the working girls got erased, making women seem like frail, put upon creatures of history till they finally burned their bras and sang Helen Reddy songs.

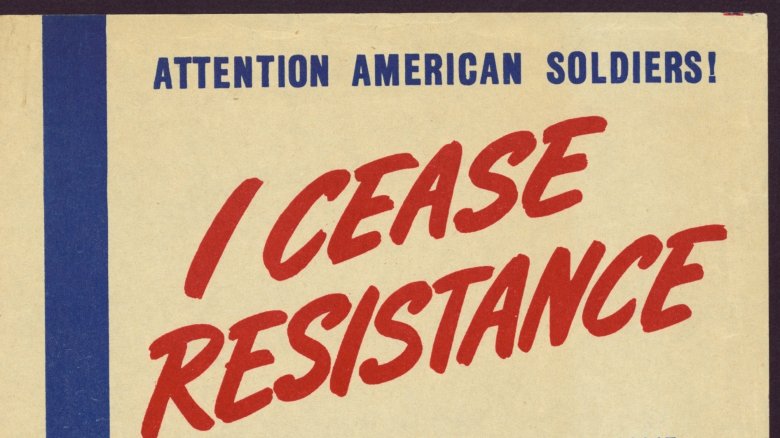

America was enthusiastic to join World War II

Even the people who marched with «No blood for oil» signs and are currently protesting drone strikes tend to still have a little fondness for World War II. Who doesn’t want to defeat a bunch of Nazis and get the chance to make fun of Germans? World War II was just too good to resist.

Even the people who marched with «No blood for oil» signs and are currently protesting drone strikes tend to still have a little fondness for World War II. Who doesn’t want to defeat a bunch of Nazis and get the chance to make fun of Germans? World War II was just too good to resist.

But Americans at the time weren’t so enthusiastic. President Franklin Roosevelt was the most vocal supporter of the war, while oddly enough, aviator Charles Lindbergh was one of the biggest opponents. Lindbergh’s strong isolationism got him labeled as a Nazi sympathizer. It’s not exactly true, since he mostly admired Germany for their technology and economic revitalization. But he also thought white people were superior to everyone else, so honestly he was about as close to a Nazi sympathizer as you could be without donning a swastika. Lindbergh said he didn’t approve of Hitler’s treatment of Jews, but he seemed cool with everything else.

Other Americans wanted to stay out and weren’t motivated by racism. Europe seemed like another world, and we had no place in their fight. Plus, the war meant the draft was coming back, and most people weren’t interested in having a repeat of the Civil War or World War I.

College students were one of the largest contingents against the war. They figured they’d be the first to die if we headed overseas, so students at Yale formed a large isolationist group called «America First.» Members of the group included Gerald Ford, Supreme Court Justice Potter «I know it when I see it» Stewart, Gore Vidal, and John F. Kennedy. It seems like young people always fought every war. If we could go back to the college campuses during the American Revolution, we’d probably see a lot of people with «No blood for tea» signs.