An affectionate homage to one of humanity’s most original and beloved artists.

BY MARIA POPOVA

“Only an artist can tell … what it is like for anyone who gets to this planet to survive it,” James Baldwin wrote in contemplating the artist’s struggle for integrity. “Being an artist is not just about what happens when you are in the studio,” Teresita Fernández argued half a century later in her spectacular commencement address on what it means to be an artist. “The way you live, the people you choose to love and the way you love them, the way you vote … will also become the raw material for the art you make.”

Few artists have embodied this integration more fully, nor more beautifully, than Frida Kahlo (July 6, 1907–July 13, 1954).

Her singular integration of life, love, and art comes alive in Frida Kahlo: An Illustrated Biography (public library) by writer Zena Alkayat and artist Nina Cosford, part of the lovely Library of Luminaries series that gave us the illustrated biography of Virginia Woolf and that of Jane Austen.

The concise yet lyrical story follows Frida from her polio-scarred childhood in Mexico, to the nearly fatal accident that inflicted on her a lifetime of physical pain but also sparked her foray into painting, to her intense and complicated romance with Diego Rivera, to her spirited politics, to her creative and critical success as one of the most original and influential artists of the twentieth century. The call-and-response of pain and beauty emerges as the constant chorus of her life while she transforms, again and again, trauma into transcendent art.

Alkayat writes:

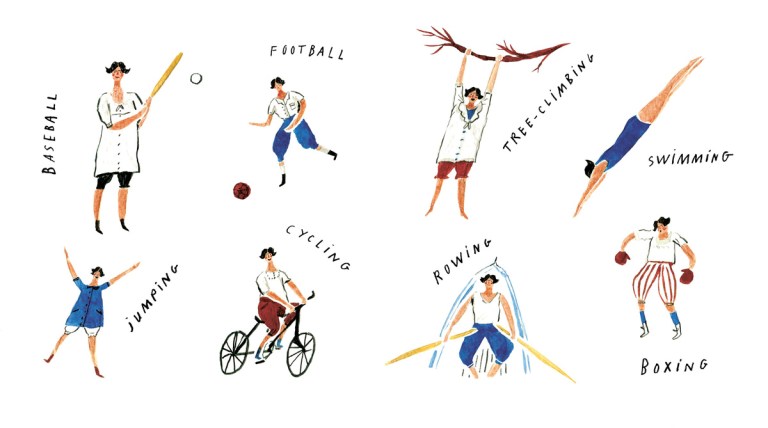

At six, Frida fell ill with polio. She was confined to her room for nine months and her right leg withered. To help her gain strength, her father encouraged her to take up sports that were usually reserved for boys.

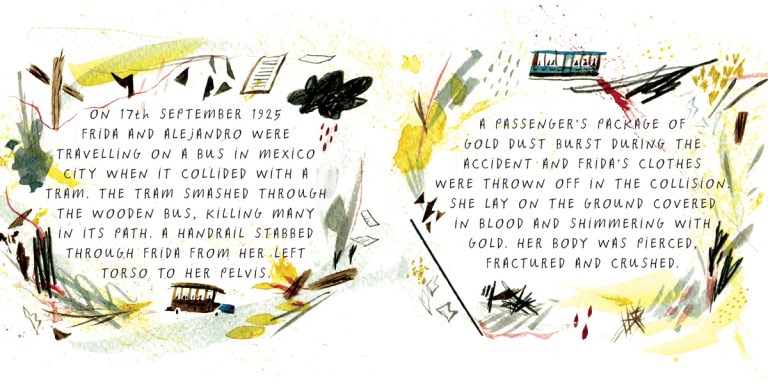

A pivotal moment in Kahlo’s life, both physically and psychologically, takes place on September 17, 1925, when 18-year-old Frida is nearly killed in a bus accident that drives a handrail diagonally into her torso, from her left ribs to her uterus. Even the gore of this tragedy has an almost mythic quality to it.

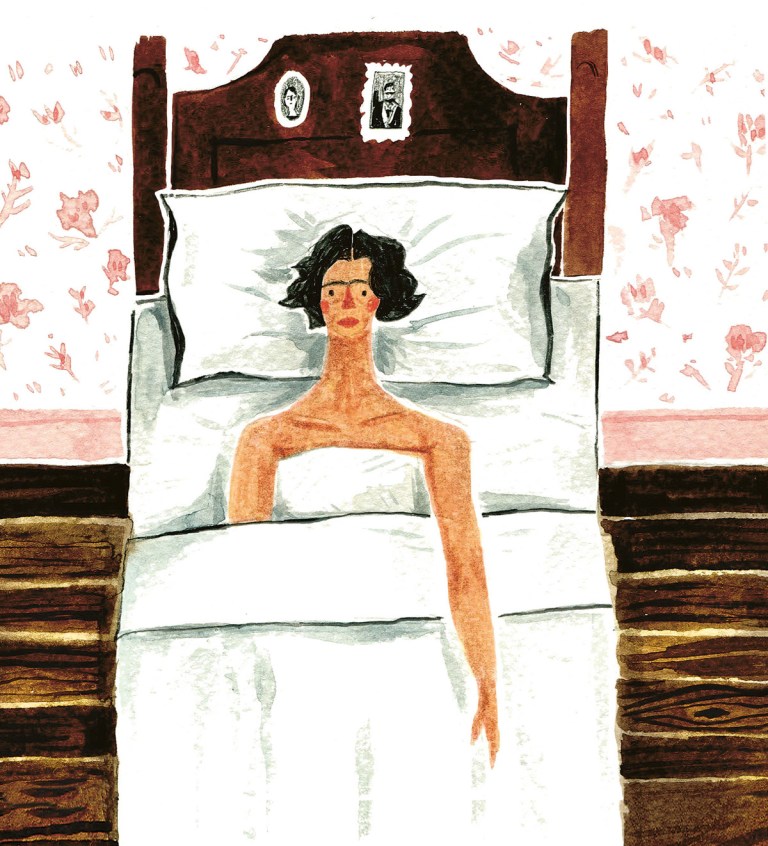

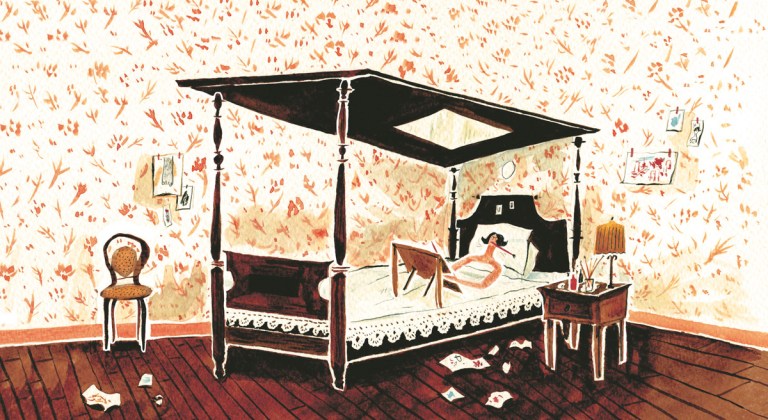

It is during the anguishing and seemingly endless recovery — to be sure, being bedridden for a month is indeed an eternity of torture for a teenager even without the excruciating physical pain — that Frida picks up painting, initially simply to distract herself. With the help of a mirror affixed to the canopy of her bed, she paints her first self-portrait — a gift for Alejandro, her first big love.

It takes Frida almost two years to walk again, and by that point she is already making a living as an artist. Her longing for mentorship and professional guidance leads her to her fateful encounter with Diego Rivera, who would become the great and greatly troubled love of her life, and the recipient of her passionate love letters.

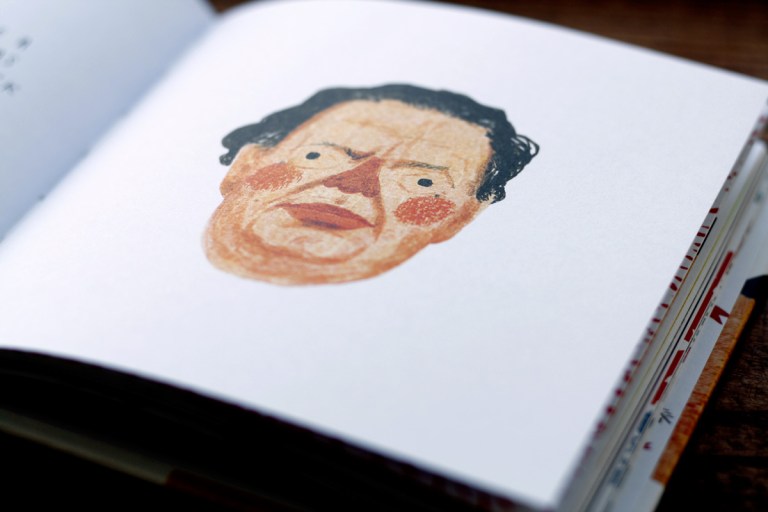

Frida married Diego on August 21, 1929. She was twenty-two, he was forty-two. She looked like a bright, beautiful bird next to the rotund, unattractive Diego. She nicknamed him “Frog-Toad.”

Diego was obsessed with his craft and prized it above all else. He encouraged Frida to devote herself to painting and to explore her own artistic style. But the young bride threw herself into being a good wife. She cooked, cleaned, and entertained.

Every lunchtime, she prepared a basket of food blanketed with flowers and delivered it to the scaffold where Diego worked.

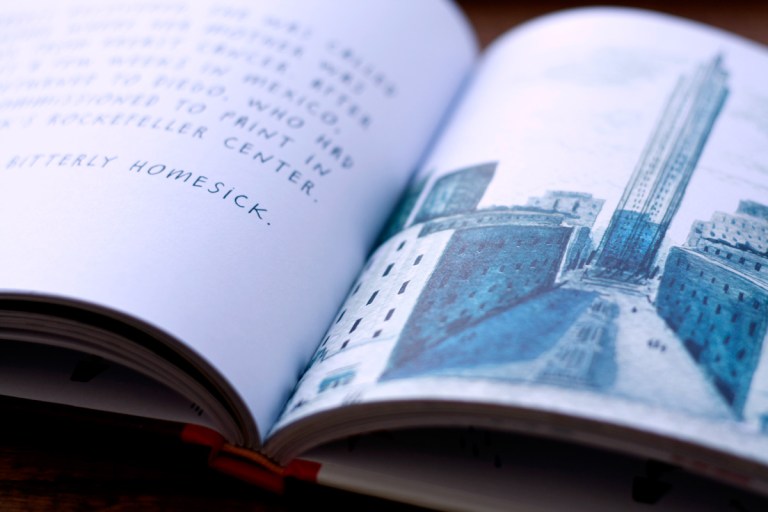

Even as the couple arrived in the United States in 1930, Frida continued to dress in vibrant traditional garb inspired by South Mexico’s Tehuana matriarchs. Every single morning, she took painstaking care with her outfit in a testament to Virginia Woolf’s case for clothing as a vehicle for our identity and values.

But her wardrobe was also dictated by the demands of her battered body and entailed an arsenal of corsets to support her fractured torso.

Frida’s life continued to be marked by pain. Her longtime longing for a child was violently severed by two miscarriages, the second of which lasted thirteen days. While still recovering, she was beckoned back home to the dying bedside of her mother, taken by breast cancer. Once again, she turned her trauma into raw material for art — something Marina Abramović articulated beautifully a generation later — and her painting took on new dimensions of expressive depth.

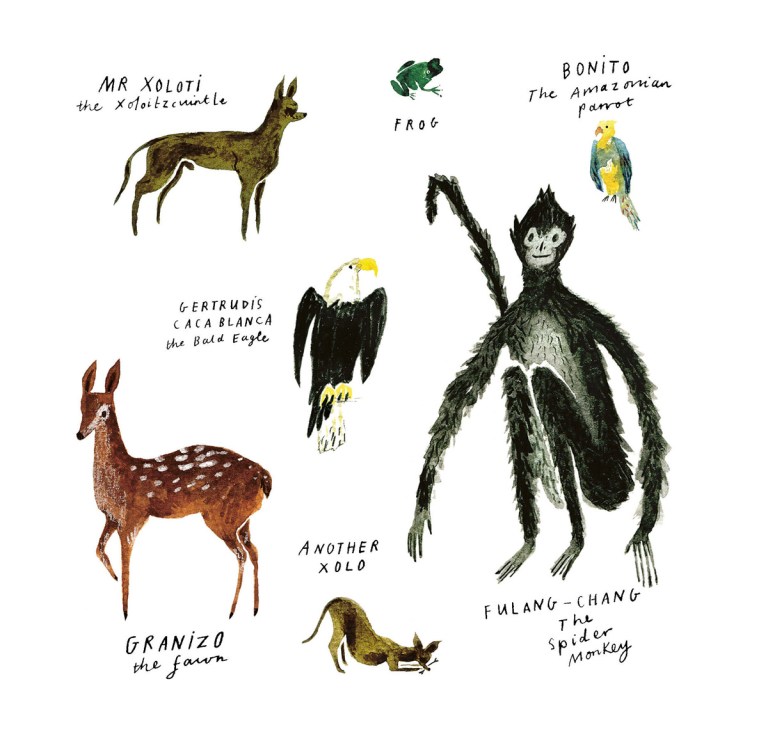

Kahlo’s tireless quest for glimmers of joy included a menagerie of exotic pets she loved dearly, perhaps because they spoke to her own sense of creaturely strangeness.

The story follows Frida’s life through her increasingly troubled marriage with Diego, their divorce and remarriage, Diego’s dalliances, and Frida’s eventual affairs with both men (including Marxist revolutionary Leon Trotsky) and women (including jazz icon Josephine Baker). Kahlo was deeply dispirited by her difficult love life, but this tumult of the heart found symbolic expression in her paintings and continued to shape her art, always so intimately entwined with her vibrant interior life.

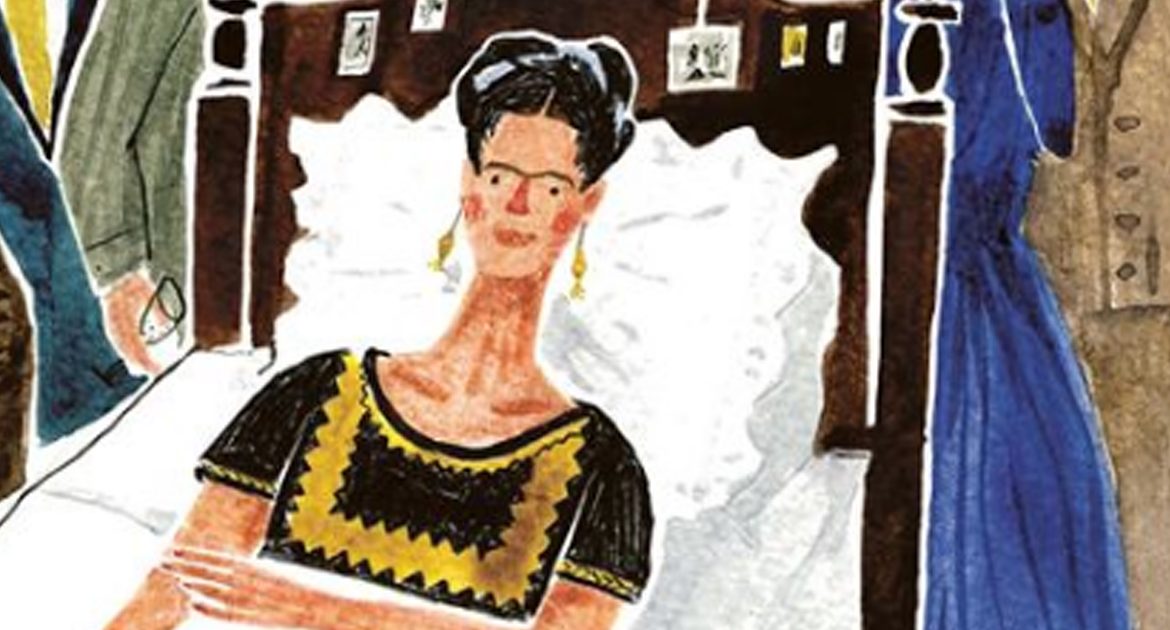

Frida’s old spark surfaced again in spring 1953 when a one-woman exhibition was arranged in her honor. Unable to walk on the day it opened, Frida sent her four-poster bed ahead of her and arrived in grand style on a stretcher. Her fans adored her, and the internationally celebrated show did much to cement her legacy as an incomparable artist.

In a sense, the bed became the womb in which Kahlo’s creative genius and legacy were gestated — she learned to paint in bed, met her greatest critical success in bed, and died in bed, in her sleep, the following summer.

Her death occasioned the kind of collective tragedy of which Borges so memorably wrote — masses of mourners grieved in public, and her final resting place at the Place of Fine Arts was entombed by a bed of red flowers.

Complement Frida Kahlo: An Illustrated Biography with the beloved artist on how love amplifies beauty, her compassionate letter to Georgia O’Keeffe after her American friend was hospitalized for a nervous breakdown, and this very different picture-book about her life and spirit, then revisit the illustrated biographies of other cultural icons: Louise Bourgeois, E.E. Cummings, Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Pablo Neruda, Jane Goodall, Albert Einstein, and Nellie Bly.