Certain relationships are charged with an intensity of feeling that incinerates the walls we habitually erect between platonic friendship, romantic attraction, and intellectual-creative infatuation.

One of the most dramatic of those superfriendships unfolded between the artists Paul Gauguin (June 7, 1848–May 8, 1903) and Vincent van Gogh (March 30, 1853–July 29, 1890), whose relationship was animated by an acuity of emotion so lacerating that it led to the famous and infamously mythologized incident in which Van Gogh cut off his own ear — an incident that marks the extreme end of what Sir Thomas Browne contemplated, two centuries earlier, as the divine heartbreak of romantic friendship.

Vincent van Gogh, “Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear,” 1889

In February of 1888, a decade after Van Gogh found his purpose, he moved to the town of Arles in the South of France. There, he exploded into a period of immense creative fertility, completing more than two hundred paintings, one hundred watercolors and sketches, and his famous Sunflowers series. But he also lived in extreme poverty and endured incessant inner turmoil, much of which related to his preoccupation with enticing Gauguin — whom he admired with unparalleled ardor (“I find my artistic ideas extremely commonplace in comparison with yours,” Van Gogh wrote) and who at the time was living and working in Brittany — to come live and paint with him. This coveted cohabitation, Van Gogh hoped, would be the beginning of a larger art colony that would serve as “a shelter and a refuge” for Post-Impressionist painters as they pioneered an entirely novel, and therefore subject to spirited criticism, aesthetic of art. Van Gogh wrote to Gauguin in early October of 1888:

I’d like to see you taking a very large share in this belief that we’ll be relatively successful in founding something lasting.

Despite his destitution, Van Gogh spent whatever money he had on two beds, which he set up in the same small bedroom. Seeking to make his modest sleeping quarters “as nice as possible, like a woman’s boudoir, really artistic,” he resolved to paint a set of giant yellow sunflowers onto its white walls. He wrote beseeching letters to Gauguin, and when the French artist sent him a self-portrait as part of their exchange of canvases, Van Gogh excitedly showed it around town as the likeness of a beloved friend who was about to come visit.

Gauguin finally agreed and arrived in Arles in mid-October, where he was to spend about two months, culminating with the dramatic ear incident.

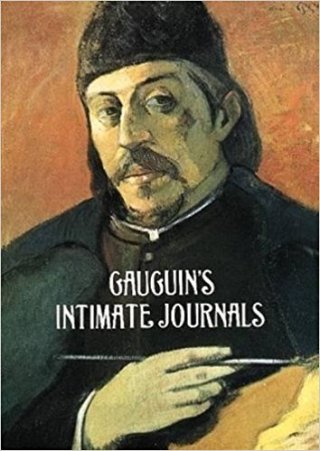

In Paul Gauguin’s Intimate Journals (public library), the French painter provides the only first-hand account of the strange, almost surreal circumstances that led to Van Gogh’s legendary self-mutilation — circumstances chronically mis-reported by most biographers and the many lay myth-weavers of popular culture, all removed from the facts of the incident by space, time, and many degrees of intimacy.

“Paul Gauguin (Man in a Red Beret)” by Vincent van Gogh, 1888 (Van Gogh Museum)

Gauguin recalls that he resisted Van Gogh’s insistent invitations for quite some time. “A vague instinct forewarned me of something abnormal,” he writes. But he was “finally overborne by Vincent’s sincere, friendly enthusiasm.” He arrived late into the night and, not wanting to wake Van Gogh, awaited dawn in a town café. The owner instantly recognized him as the friend whose likeness Van Gogh had been proudly introducing as the anticipated friend.

After Gauguin settled in, Van Gogh set out to show him the beauty and beauties of Arles, though Gauguin found that he “could not get up much enthusiasm” for the local women. By the following day, they had begun work. Gauguin marveled at Van Gogh’s clarity of purpose. “I don’t admire the painting but I admire the man,” he wrote. “He so confident, so calm. I so uncertain, so uneasy.” Gauguin foreshadows the tumult to come:

Between two such beings as he and I, the one a perfect volcano, the other boiling too, inwardly, a sort of struggle was preparing. In the first place, everywhere and in everything I found a disorder that shocked me. His colour-box could hardly contain all those tubes, crowded together and never closed. In spite of all this disorder, this mess, something shone out of his canvases and out of his talk, too…. He possessed the greatest tenderness, or rather the altruism of the Gospel.

Soon, the two men merged their finances, which succumbed to the same sort of disorder. They began sharing household duties — Van Gogh secured their provisions and Gauguin cooked — and lived together for what Gauguin would later recall as an eternity. (In reality, it was nine weeks.) From the distance of years, he reflects on the experience in his journal:

In spite of the swiftness with which the catastrophe approached, in spite of the fever of work that had seized me, the time seemed to me a century.

Though the public had no suspicion of it, two men were performing there a colossal work that was useful to them both. Perhaps to others? There are some things that bear fruit.

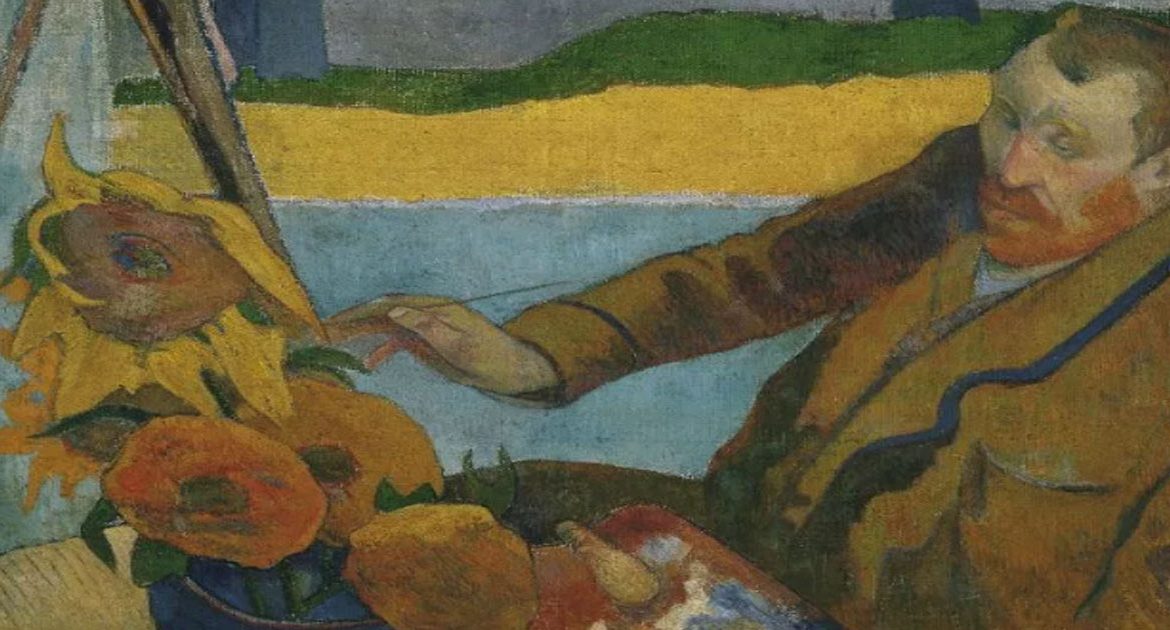

“The Painter of Sunflowers (Portrait of Vincent van Gogh)” by Paul Gauguin, 1888 (Van Gogh Museum)

Despite the frenzied enthusiasm and work ethic with which Van Gogh approached his paintings, Gauguin saw them as “nothing but the mildest of incomplete and monotonous harmonies.” So he set out to do what Van Gogh had invited him there to do — serve as mentor and master. (Gauguin was the only person whom Van Gogh ever addressed as “Master.”) He found the younger artist hearteningly receptive to criticism:

Like all original natures that are marked with the stamp of personality, Vincent had no fear of the other man and was not stubborn.

From that day on, Gauguin recounts, Van Gogh — “my Van Gogh” — began making “astonishing progress,” found his voice as an artist and came into his own style, cultivating the singular sense of color and light for which he is now remembered. But then something shifted — having found his angels, Van Gogh had also uncovered his demons. Gauguin recounts the tempestuous emotional climates that seemed to sweep over Van Gogh unpredictably — the beginning of his descent into the mental illness that would be termed bipolar disorder a century later:

During the latter days of my stay, Vincent would become excessively rough and noisy, and then silent. On several nights I surprised him in the act of getting up and coming over to my bed. To what can I attribute my awakening just at that moment?

At all events, it was enough for me to say to him, quite sternly, “What’s the matter with you, Vincent?” for him to go back to bed without a word and fall into a heavy sleep.

Van Gogh soon completed a self-portrait he considered to be a painting of himself “gone mad.” That evening, the two men headed to the local café. Gauguin recounts the astounding scene that followed, equal parts theatrical and full of sincere human tragedy:

[Vincent] took a light absinthe. Suddenly he flung the glass and its contents at my head. I avoided the blow and, taking him boldly in my arms, went out of the café, across the Place Victor Hugo. Not many minutes later, Vincent found himself in his bed where, in a few seconds, he was asleep, not to awaken again till morning.

When he awoke, he said to me very calmly, “My dear Gauguin, I have a vague memory that I offended you last evening.”

Answer: “I forgive you gladly and with all my heart, but yesterday’s scene might occur again and if I were struck I might lose control of myself and give you a choking. So permit me to write to your brother and tell him that I am coming back.

But the previous day’s drama was only a tremor of the earthquake to come that fateful evening, two days before Christmas 1888. “My God, what a day!” Gauguin exclaims as he chronicles what happened when he decided to take a solitary walk after dinner to clear his head:

I had almost crossed the Place Victor Hugo when I heard behind me a well-known step, short, quick, irregular. I turned about on the instant as Vincent rushed toward me, an open razor in his hand. My look at the moment must have had great power in it, for he stopped and, lowering his head, set off running towards home.

Gauguin laments that in the years since, he has been frequently bedeviled by the regret that he didn’t chase Van Gogh down and disarm him. Instead, he checked into a local hotel and went to bed, but he found himself so agitated that he couldn’t fall asleep until the small hours of the morning. Upon rising at half past seven, he headed into town, where he was met with an improbable scene:

Reaching the square, I saw a great crowd collected. Near our house there were some gendarmes and a little gentleman in a melon-shaped hat who was the superintendent of police.

This is what had happened.

Van Gogh had gone back to the house and had immediately cut off his ear close to the head. He must have taken some time to stop the flow of blood, for the day after there were a lot of wet towels lying about on the flag-stones in the two lower rooms. The blood had stained the two rooms and the little stairway that led up to our bedroom.

When he was in a condition to go out, with his head enveloped in a Basque beret which he had pulled far down, he went straight to a certain house where for want of a fellow-countrywoman one can pick up an acquaintance, and gave the manager his ear, carefully washed and placed in an envelope. “Here is a souvenir of me,” he said.

That “certain house” was, of course, the brothel Van Gogh frequented, where he had found some of his models. After handing the madam his ear, he ran back home and went straight to sleep, shutting the blinds and setting a lamp on the table by the window. A crowd of townspeople gathered below within minutes, discomfited and abuzz with speculation about what had happened. Gauguin writes:

I had no faintest suspicion of all this when I presented myself at the door of our house and the gentleman in the melon-shaped hat said to me abruptly and in a tone that was more than severe, “What have you done to your comrade, Monsieur?”

“I don’t know…”

“Oh, yes… you know very well… he is dead.”

I could never wish anyone such a moment, and it took me a long time to get my wits together and control the beating of my heart.

Anger, indignation, grief, as well as shame at all these glances that were tearing my person to pieces, suffocated me, and I answered, stammeringly: “All right, Monsieur, let me go upstairs. We can explain ourselves there.”

Then in a low voice I said to the police superintendent: “Be kind enough, Monsieur, to awaken this man with great care, and if he asks for me tell him I have left for Paris; the sight of me might prove fatal to him.”

I must own that from this moment the police superintendent was as reasonable as possible and intelligently sent for a doctor and a cab.

Once awake, Vincent asked for his comrade, his pipe and his tobacco; he even thought of asking for the box that was downstairs and contained our money, — a suspicion, I dare say! But I had already been through too much suffering to be troubled by that.

Vincent was taken to a hospital where, as soon as he had arrived, his brain began to rave again.

All the rest everyone knows who has any interest in knowing it, and it would be useless to talk about it were it not for that great suffering of a man who, confined in a madhouse, at monthly intervals recovered his reason enough to understand his condition and furiously paint the admirable pictures we know.

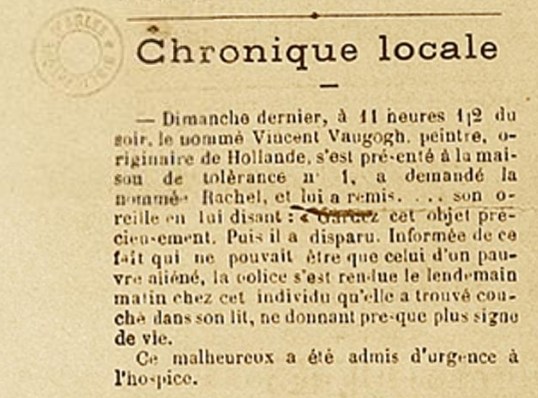

Newspaper report from December 30, 1888: ‘Last Sunday night at half past eleven a painter named Vincent Van Gogh, appeared at the maison de tolérance No 1, asked for a girl called Rachel, and handed her … his ear with these words: ‘Keep this object like a treasure.’ Then he disappeared. The police, informed of these events, which could only be the work of an unfortunate madman, looked the next morning for this individual, whom they found in bed with scarcely a sign of life. The poor man was taken to hospital without delay.’

With pressure from alarmed neighbors and local police, Van Gogh was soon committed into an insane asylum. From there, he wrote to Gauguin about the sundering tension between his desire to return to painting and his sense that his mental illness was incurable, but then added: “Aren’t we all mad?”

Seventeen months later, he took his own life — a tragedy Gauguin recounts with the tenderness of one who has loved the lost:

He sent a revolved shot into his stomach, and it was only a few hours later that he died, lying in his bed and smoking his pipe, having complete possession of his mind, full of the love of his art and without hatred for others.

Complement this particular portion of the forgotten treasure Paul Gauguin’s Intimate Journals with astrophysicist Janna Levin on madness and genius, poet Robert Lowell on what it’s like to be bipolar, and neuropsychiatrist Nancy Andreasen on the relationship between creativity and mental illness, then revisit Gauguin’s advice on overcoming rejection and Van Gogh on love and art, how relationships refine us, and his never-before-revealed sketchbooks.