Few things in creative culture are more enchanting than an artist’s interpretation of a beloved book. There is Maurice Sendak’s rare and formative art for William Blake’s “Songs of Innocence,” William Blake’s paintings for Milton’s Paradise Lost, Picasso’s 1934 drawings for a naughty ancient Greek comedy, Matisse’s 1935 etchings for Ulysses, and Salvador Dalí’s literary illustrations for Cervantes’s Don Quixote, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and the essays of Montaigne.

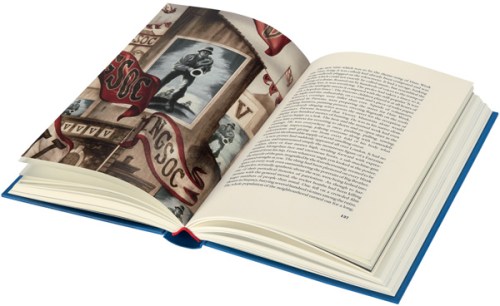

Since 1947, The Folio Society has served as the premier patron saint of such contemporary cross-pollinations of great art and great literature. Now comes a gorgeous slipcase edition of the George Orwell classic Nineteen Eighty-Four (public library), illustrated by Jonathan Burton — a book both timeless and extraordinarily, chillingly timely as we confront the aftermath of the NSA fallout, and the best visual interpretation of Orwell since Ralph Steadman’s spectacular illustrations for Animal Farm.

In the introduction, Guardian editor-in-chief Alan Rusbridger — who broke the Edward Snowden story in a masterwork of journalism and stood up to real-life Big Brother by refusing to hand over Snowden’s data to the government — explores the parallels, contrasts, and essential civic discourse springing from the difference between the two camps:

As the full impact of the Snowden revelations sank in, many people made the same connection, and Amazon announced a dramatic rise in sales of Nineteen Eighty-Four. To some, the young NSA analyst had revealed a world which was near-Orwellian; others thought that he had described a state of affairs that Orwell could barely have imagined. Just before Christmas 2013 a US District Judge, Richard Leon, pronounced the NSA’s surveillance capabilities to be “almost Orwellian.” Orwellian, beyond Orwellian, not-quite Orwellian. As the debate ricocheted around the world there soon developed the counter-school: not at all Orwellian. Or even, “Orwell got it wrong,” ignoring Thomas Pynchon’s caution about Nineteen Eighty-Four that “prophecy and prediction are not quite the same.” The not-Orwellians found it offensive that a book describing a totalitarian dystopia should be confused with the efforts of one of the most open, liberal democracies in the world to defend itself. And so the debate about the “Orwellian” nature of what the NSA was up to became a proxy for discussion of the issue itself.

But the book’s most important legacy, as Rusbridger suggests, lives in precisely that limbo between what Orwell got right and what he got wrong — a testament to “the unknowable question of what future purpose technology might be put to,” the darker answers to which we must at the very least acknowledge, even as we strive to offer more ennobling ones.

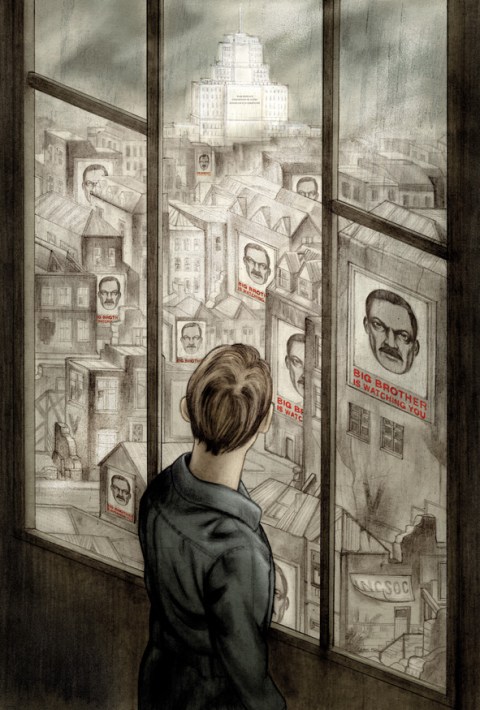

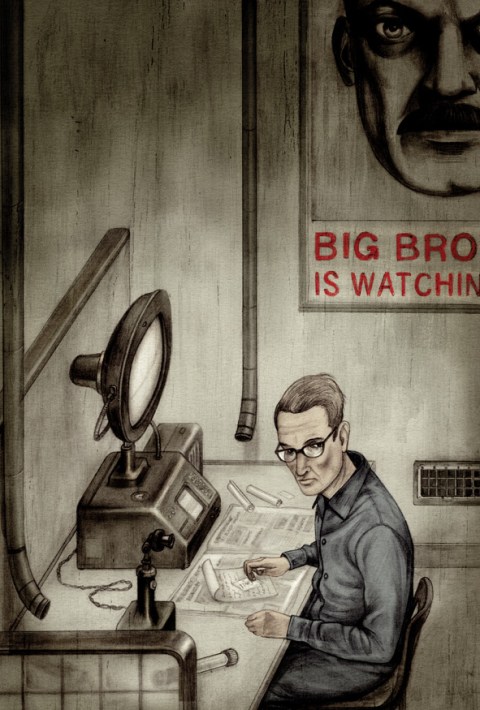

‘There seemed to be no colour in anything, except the posters that were plastered everywhere.’

‘On it was written, in a large unformed handwriting: I love you.’

‘He knelt down before her and took her hands in his.’

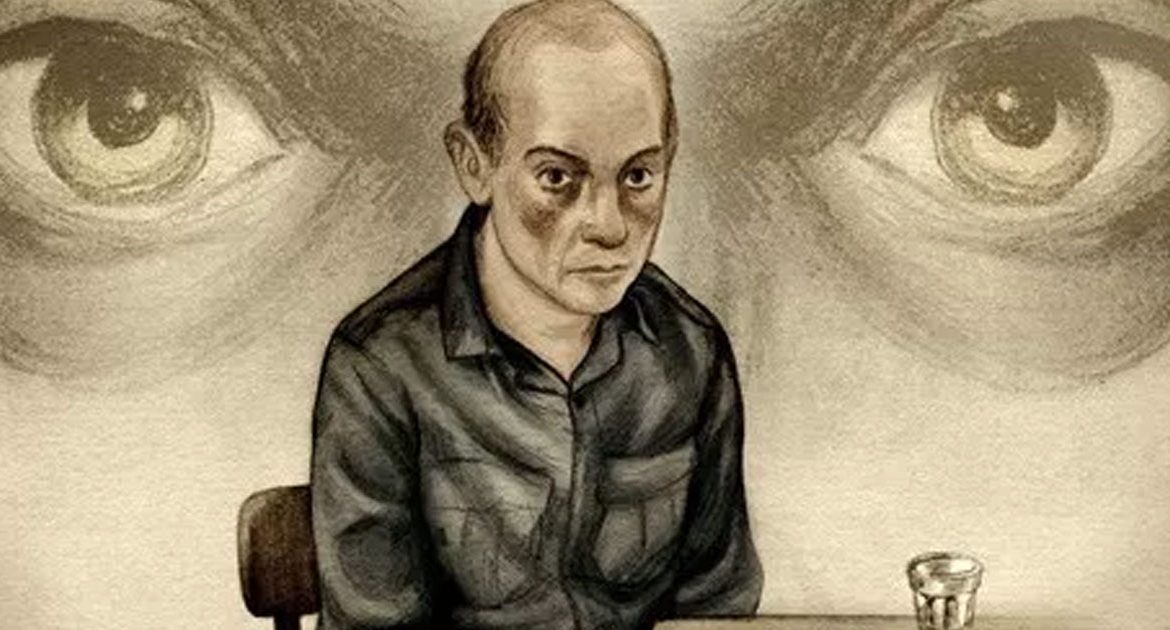

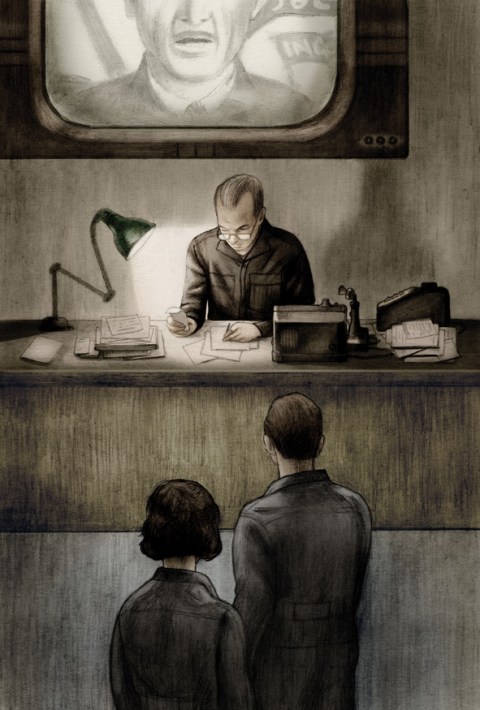

‘At the far end of the room, O’Brien was sitting at a table under a green-shaded lamp.’

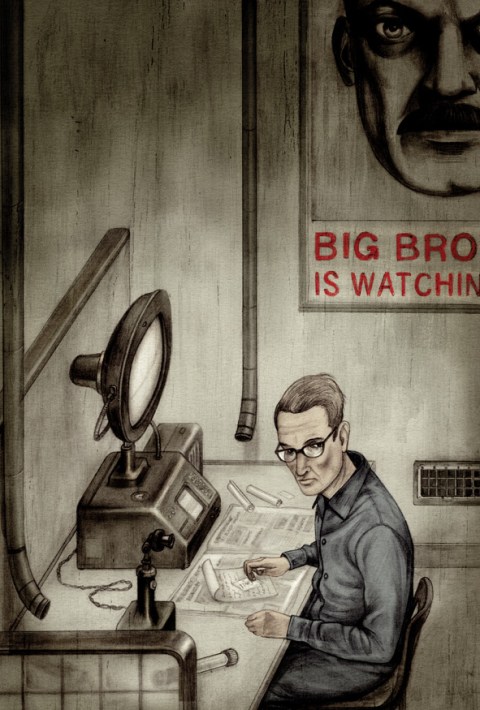

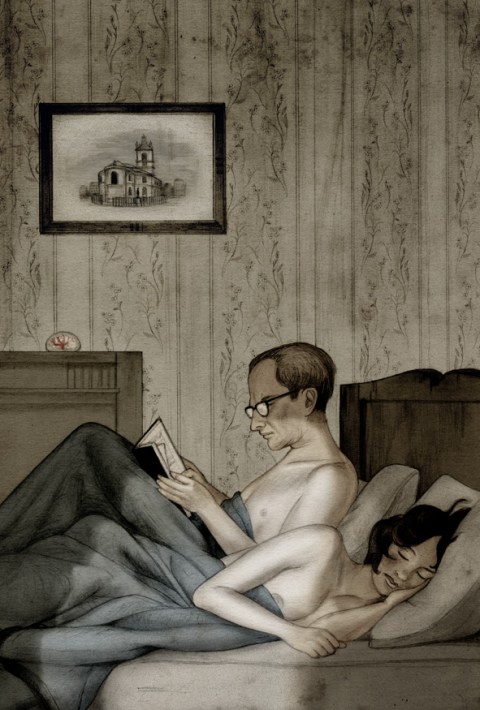

‘He propped the book against his knees and began reading: Chapter I. Ignorance is Strength.’

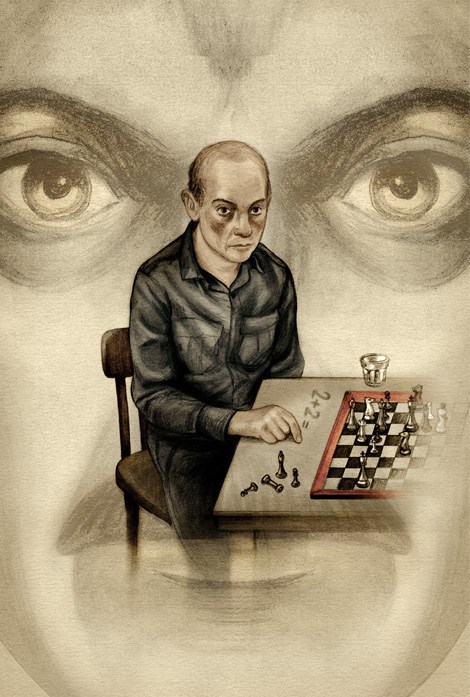

‘Almost unconsciously he traced with his finger in the dust on the table.’

Complement Nineteen Eighty-Four with two other Folio Society favorites — artist Mimmo Paladino’s stunning etchings for Ulysses and John Vernon Lord’s visually gripping take on Finnegans Wake — then revisit Orwell on the freedom of the press, why writers write, the four questions a great writer must answer, and his eleven golden rules for the perfect cup of tea.