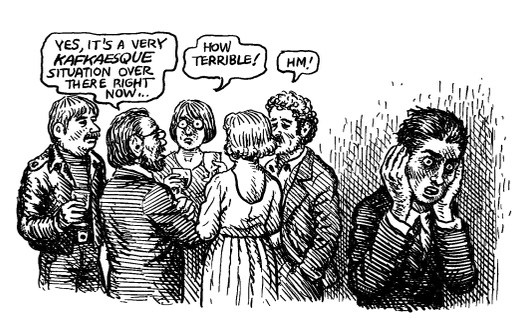

…and why “Kafkaesque” doesn’t mean what you think it does.

After revolutionizing album covers in the 1960s and 1970s, legendary cartoonist and counterculture icon R. Crumb (b. August 30, 1943) sought out his creative kin in another realm of art, traversing the boundaries of life and death to embark on a series of posthumous “collaborations” with some of literature’s most revered irreverents. He illustrated two short books by Bukowski, visualized Philip K. Dick’s hallucinatory exegesis, and adapted Sartre into a comic.

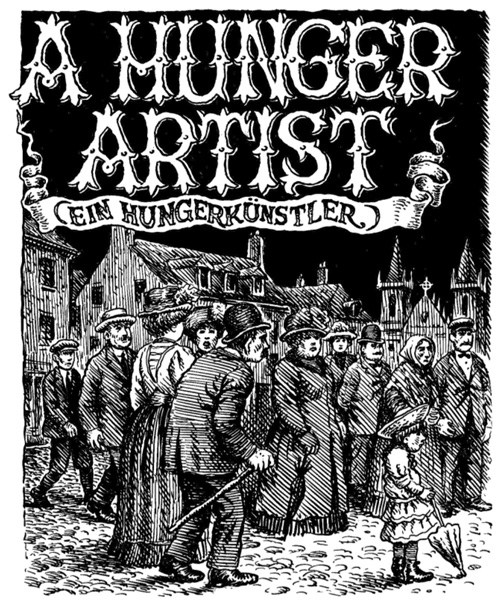

But his greatest, most grimly glorious contribution to the literary canon came with the 2007 release of Kafka (public library) — a succinct and illuminating biography by David Zane Mairowitz, covering everything from Kafka’s the troubled relationship with his emotionally abusive father to his fear of women to his lifelong love affair with his own death to the cultural misunderstandings in which the term “Kafkaesque” is mired.

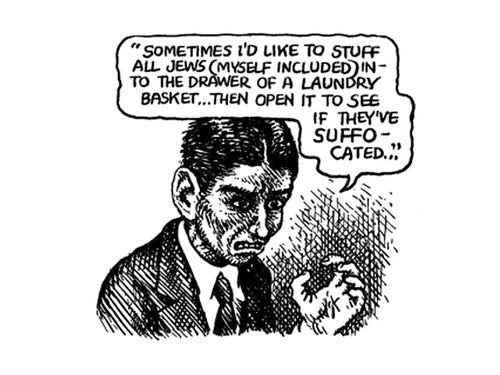

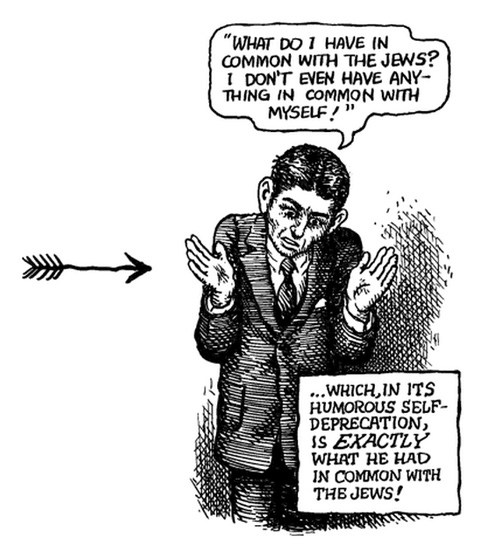

In one particularly poignant passage, Mairowitz examines Kafka’s conflicted sense of identity — a function of the core human tendencies Margaret Mead and James Baldwin so elegantly captured decades earlier — and considers the author’s coping mechanisms amid Prague’s anti-Semitic cultural climate:

Franz Kafka was never one of those harassed or beaten up on the streets because he was, or simply looked like, a Jew. Yet, however much he may have retired into himself and pushed these events out of direct reach, it would have been impossible, as for most Jews, to absent himself intellectually from the collective fate.

Like all assimilated Jews, one of the things he had to “assimilate” was a measure of “healthy anti-Semitism.” Most Jews of that time (or any other) absorbed the daily menace of anti-Semitism and turned it inward toward themselves. Kafka was no exception to feelings of Jewish self-hatred.

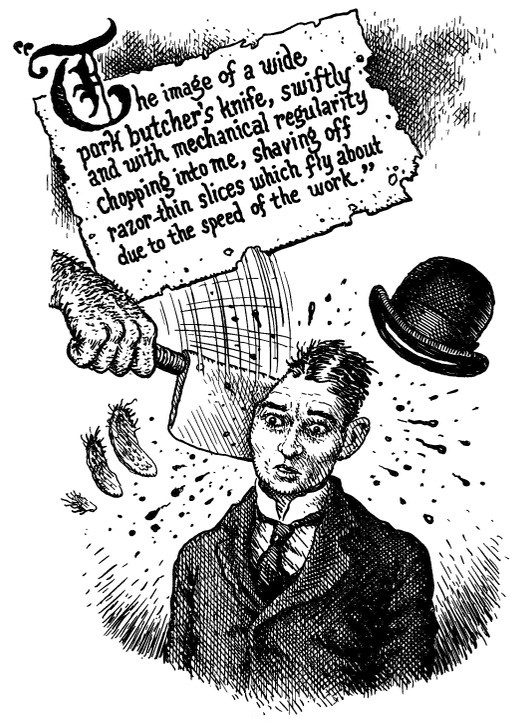

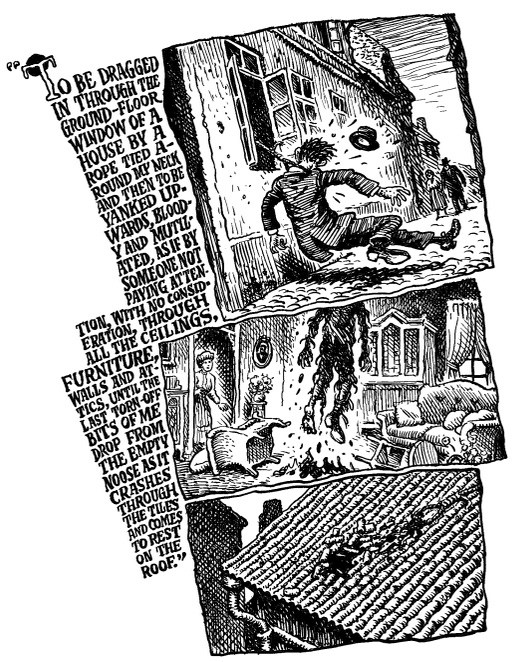

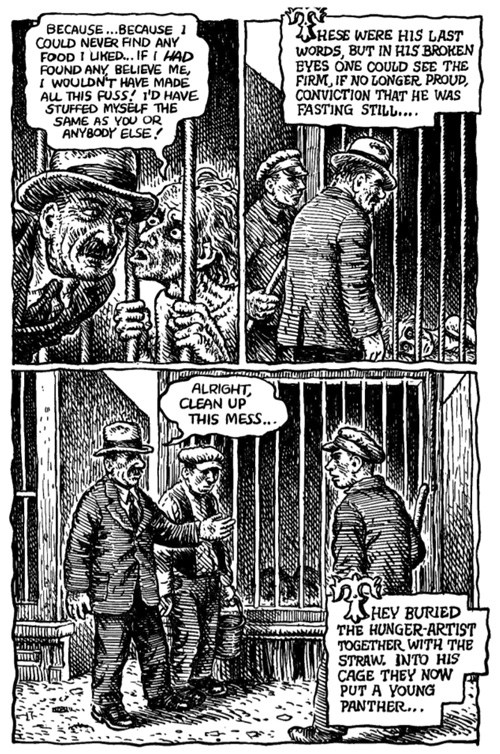

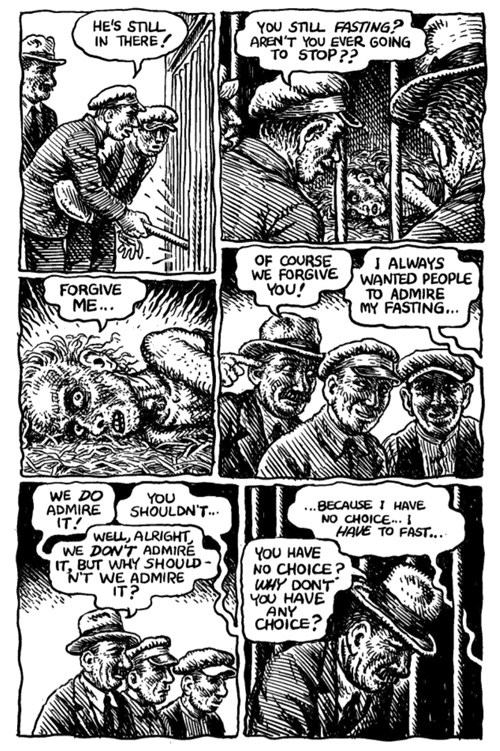

But sooner or later, even the most hateful of Jewish self-hatreds has to turn around and laugh at itself. In Kafka, the duality of dark melancholy and hilarious self-abasement is nearly always at work. “Kafkaesque” is usually swollen with notions of terror and bitter anguish. But Kafka’s stories, however grim, are nearly always also … funny.

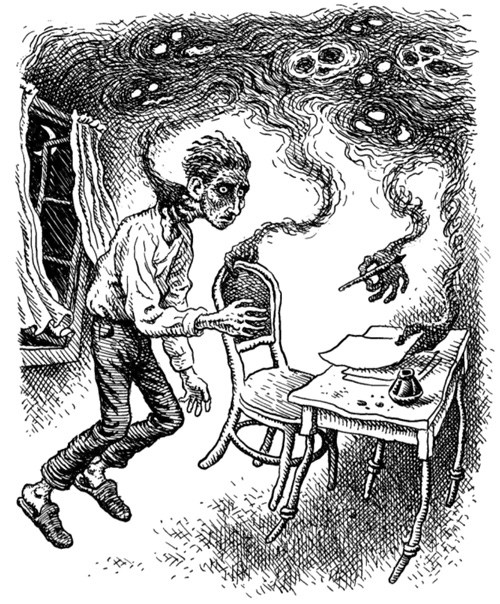

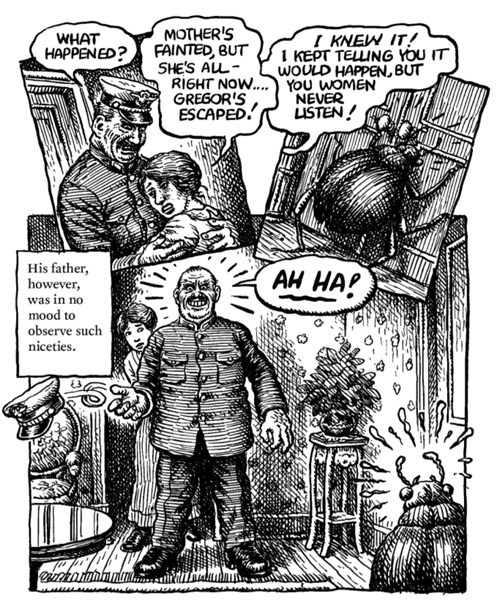

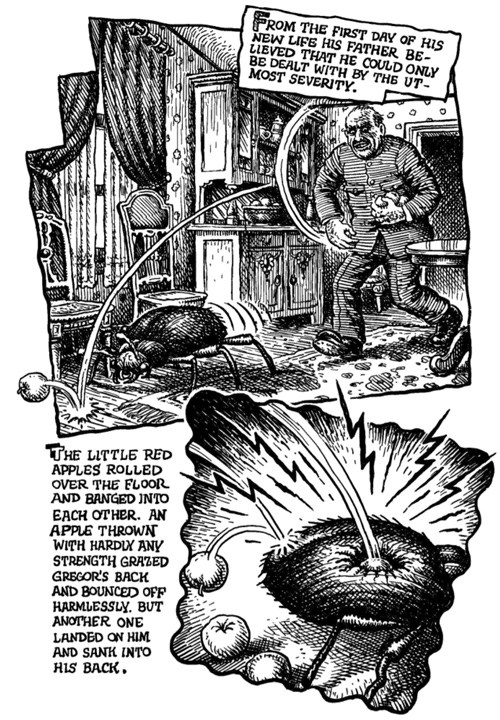

Mairowitz and Crumb also explore how Kafka’s relationship with his tyrannical father — whom 36-year-old Franz eventually attempted to confront in a harrowing letter — shaped his writing, including his most famous work, “The Metamorphosis.”

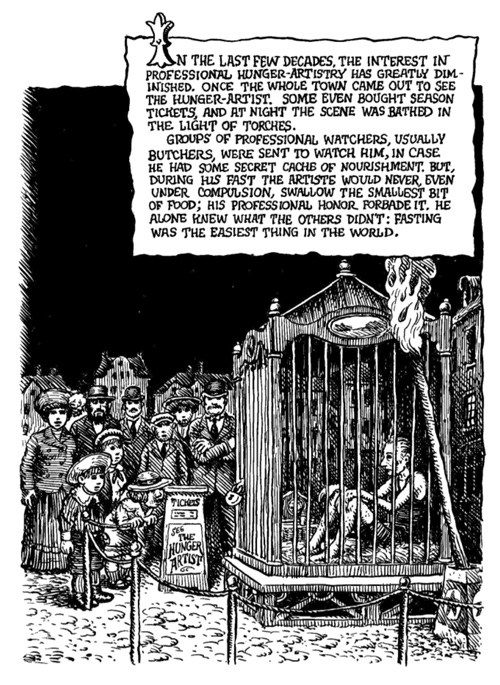

These grim parallels between Kafka’s lived experience and his fictional worlds continued until his death, even through his final moments — in June of 1924, while dying of tuberculosis-induced starvation, he was busy correcting the galley-proofs for his story collection A Hunger Artist, the publication of which several months later he never lived to see.

Complement the Crumb-crusted Kafka with the celebrated author on what books do for the human soul, his beautiful and heartbreaking love letters, and My First Kafka, a most unusual and imaginative adaptation of Kafka for kids.