“Compassion,” Karen Armstrong wrote in her stirring meditation on the true meaning of the Golden Rule, “asks us to look into our own hearts, discover what gives us pain, and then refuse, under any circumstance whatsoever, to inflict that pain on anybody else.” But when our own hearts are gripped with the threat and terror of imminent pain, how can we step outside this fear-fraught circumstance and consider, with kindness and openhearted goodwill, the reality of another?

That’s what the wise and wonderful Oliver Sacks (July 9, 1933–August 30, 2015) captures in one of the many ennobling anecdotes in On the Move: A Life (public library) — his altogether magnificent memoir of love, lunacy, and a life fully lived.

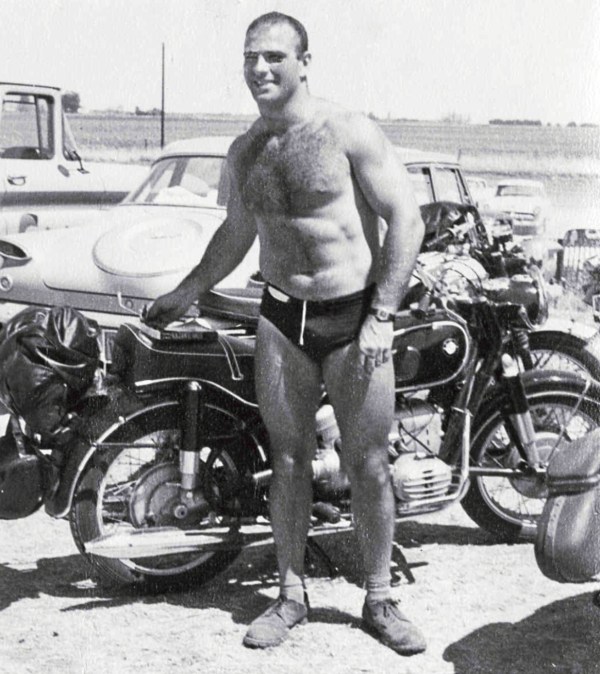

He recounts an incident from the spring of 1963, in the heyday of motorcycling and weightlifting obsession, embedded in which is an allegory of the singular genius that would come to define his career and legacy — the delicate and demanding art of peering into another’s mind with empathetic curiosity and seeing the vulnerable humanity that animates it.

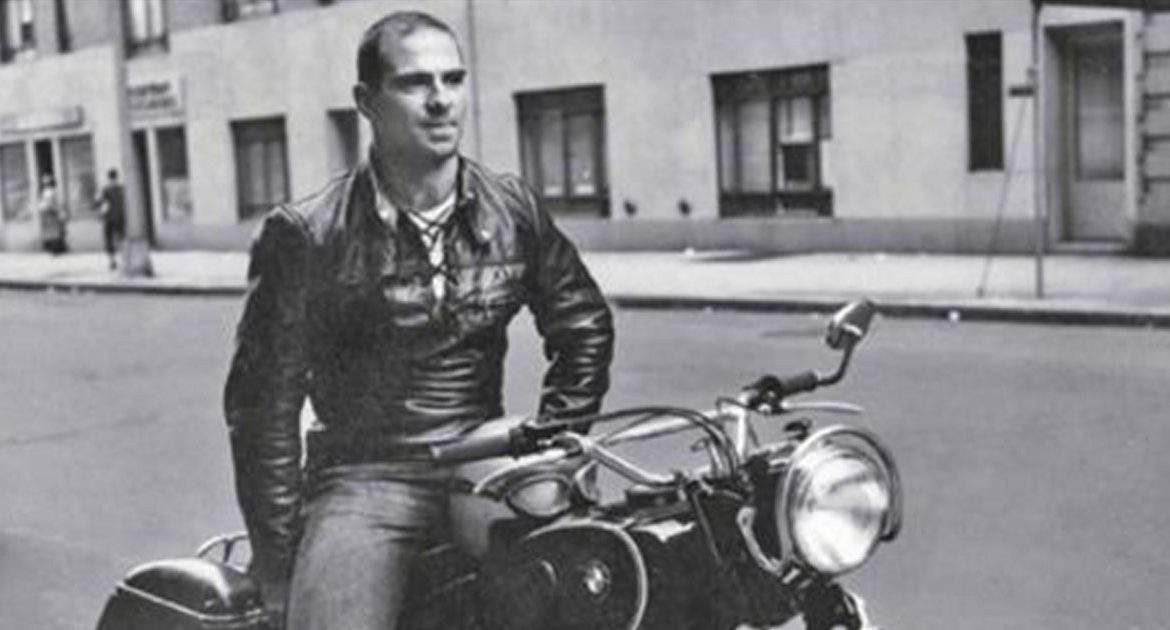

Dr. Sacks at Muscle Beach with his beloved BMW motorcycle, 1960s

Dr. Sacks writes:

I was riding along Sunset Boulevard at a leisurely pace, enjoying the weather — it was a perfect spring day — and minding my own business. Seeing a car behind me in my driving mirror, I motioned the driver to overtake me. He accelerated, but when he was parallel with me, he suddenly veered towards me, making me swerve to avoid a collision. It didn’t occur to me that this was deliberate; I thought the driver was probably drunk or incompetent. Having overtaken me, the car then slowed down. I slowed, too, until he motioned me to pass him. As I did so, he swung into the middle of the road, and I avoided being sideswiped by the narrowest margin. This time there was no mistaking his intent.

I have never started a fight. I have never attacked anyone unless I have been attacked first. But this second, potentially murderous attack enraged me, and I resolved to retaliate. I kept a hundred yards or more behind the car, just out of his line of sight, but prepared to leap forward if he was forced to stop at a traffic light. This happened when we got to Westwood Boulevard. Noiselessly — my bike was virtually silent — I stole up on the driver’s side, intending to break a window or score the paintwork on his car as I drew level with him. But the window was open on the driver’s side, and seeing this, I thrust my fist through the open window, grabbed his nose, and twisted it with all my might; he let out a yell, and his face was all bloody when I let go. He was too shocked to do anything, and I rode on, feeling I had done no more than his attempt on my life had warranted.

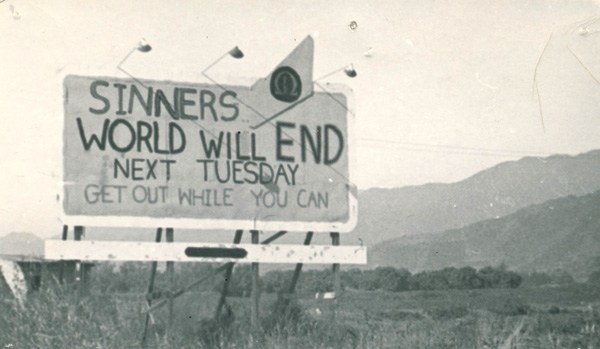

Photograph by Oliver Sacks, 1960s (Courtesy of Dr. Sacks / Kate Edgar for Brain Pickings)

Shortly after this heart-stopping encounter, Dr. Sacks found himself in a strikingly similar incident while driving to San Francisco on a desert road. An aggressive driver suddenly appeared onto the empty expanse and, moving at 90 mph, deliberately forced the motorcycle off the road. What happened next reveals Dr. Sacks as a sort of gentle giant, both deeply human in his capacity for fury and in possession of superhuman empathetic sensitivity:

By a sort of miracle, I managed to hold the bike upright, throwing up a huge cloud of dust, and regained the road. My attacker was now a couple of hundred yards ahead. Rage more than fear was my chief reaction, and I snatched a monopod from the luggage rack (I was very keen on landscape photography at the time and always traveled with camera, tripod, monopod, etc., lashed to the bike). I waved it round and round my head, like the mad colonel astride the bomb in the final scene of Dr. Strangelove. I must have looked crazy — and dangerous — for the car accelerated. I accelerated too, and pushing the engine as much as I could, I started to overtake it. The driver tried to throw me off by driving erratically, suddenly slowing, or switching from side to side of the empty road, and when that failed, he took a sudden side road in the small town of Coalinga — a mistake, because he got into a maze of smaller roads with me on his tail and finally got trapped in a cul-de-sac. I leapt off the bike (all 260 pounds of me) and rushed towards the trapped car, waving the monopod. Inside the car I saw two teenage couples, four terrified people, but when I saw their youth, their helplessness, their fear, my fist opened and the monopod fell out of my hand.

I shrugged my shoulders, picked up the monopod, walked back to the bike, and motioned them on. We had all, I think, had the fright of our lives, felt the nearness of death, in our foolish, potentially fatal duel.

On the Move, for reasons articulated here, remains one of the most moving books I’ve ever read. Complement this particular passage with Jane Goodall on empathy and Brené Brown on the crucial difference between empathy and sympathy, then revisit Oliver Sacks on storytelling and the curious psychology of writing, the paradoxical power of music, and this final farewell to the beloved science-storyteller.