“I would like to tell you every thing that happened to me since the last time we saw each other, but most of them are sad and you mustn’t know sad things now.”

There is something uncommonly heartening about bearing witness to the virtuous cycle of support and mutual appreciation between two creative luminaries — elevating epistolary exchanges like those between Hermann Hesse and Thomas Mann, Mark Twain and Helen Keller, Ursula Nordstrom and Maurice Sendak, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman. They seem to remind us that, contrary to the toxic myth of the solitary genius, creative culture is propelled by the power of scenius, by the goodwill and generosity of kindred spirits, by tangible reminders that we belong to a human enterprise larger than we are.

One of the most touching such exchanges was between two of the greatest artists and most remarkable women the world has ever known — Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keeffe. Both were prolific letter writers — Kahlo in her passionate illustrated love letters to Diego Rivera, and O’Keeffe in her equally passionate love letters to Alfred Stieglitz, her lifelong correspondence with her best friend, and her emboldening missives to Sherwood Anderson. But what Kahlo wrote to O’Keeffe in 1933 was a wholly different kind of epistolary and human magic.

Even though the Mexican painter had herself been dealt an unfair hand — including a miscarriage just a few months earlier, her mother’s recent death, and more than thirty operations over the course of her life after a serious traffic accident during adolescence sent an iron rod through her stomach and uterus — Kahlo didn’t hesitate to reach out with a beam of compassion during O’Keeffe’s moment of crisis. Shortly after the American painter was hospitalized for a nervous breakdown and instructed by doctors not to paint for a year, Kahlo sent her an epitome of what Virginia Woolf so aptly called “the humane art.”

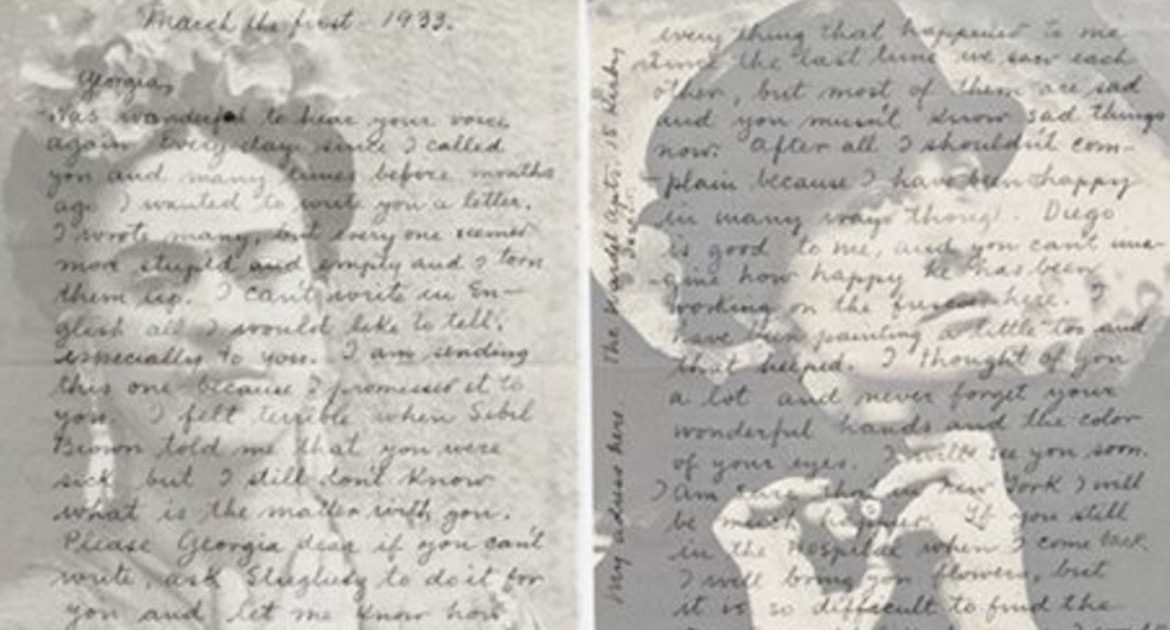

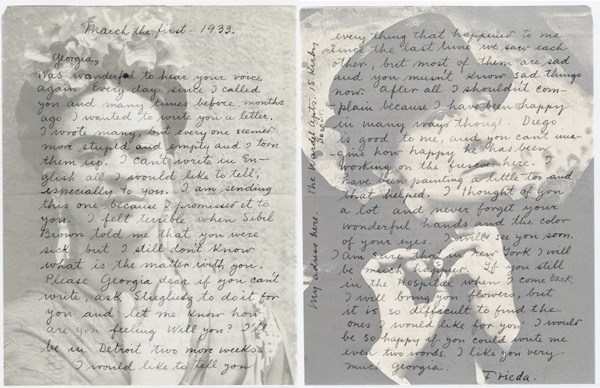

In a letter from March 1, 1933, preserved by the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale, Kahlo writes:

Georgia,

Was wonderful to hear your voice again. Every day since I called you and many times before months ago I wanted to write you a letter. I wrote you many, but every one seemed more stupid and empty and I torn them up. I can’t write in English all that I would like to tell, especially to you. I am sending this one because I promised it to you. I felt terrible when Sybil Brown told me that you were sick but I still don’t know what is the matter with you. Please Georgia dear if you can’t write, ask Stieglitz to do it for you and let me know how are you feeling will you? I’ll be in Detroit two more weeks. I would like to tell you every thing that happened to me since the last time we saw each other, but most of them are sad and you mustn’t know sad things now. After all I shouldn’t complain because I have been happy in many ways though. Diego is good to me, and you can’t imagine how happy he has been working on the frescoes here. I have been painting a little too and that helped. I thought of you a lot and never forget your wonderful hands and the color of your eyes. I will see you soon. I am sure that in New York I will be much happier. If you still in the hospital when I come back I will bring you flowers, but it is so difficult to find the ones I would like for you. I would be so happy if you could write me even two words. I like you very much Georgia.

Frieda

What’s especially interesting is the simultaneous mirroring and reversing of circumstances pertaining to the relationship between art and mental health. Kahlo had actually first begun painting while recovering, immobile in bed, from the brutal accident that nearly killed her. At the time of their 1933 correspondence, O’Keeffe was doing the opposite — recovering in bed from brutally overextending herself in art. But this wasn’t the only reversal between the two. Citing the letter in her book Carr, O’Keeffe, Kahlo: Places of Their Own (public library), Sharyn Rohlfsen Udal — who suggests that Kahlo, with her long history of affairs with both men and women, may have been interested in something more than friendship with O’Keeffe — writes:

The next confirmed record of the O’Keeffe–Kahlo contact was through their mutual friend Rose Covarrubias, who took O’Keeffe to visit Kahlo (confined to her bed in Coyoacan after a year-long hospitalization) twice during O’Keeffe’s 1951 visit to Mexico. It is an interesting reversal of roles from the 1933 contact, when it was O’Keeffe who was ill, Kahlo the solicitous visitor.

And that, perhaps, is the point — a palpable reminder that the history of arts and letters is strewn with these barely visible threads of mutuality, generosity, and goodwill, which stand as the most steadfast support structure for the creative spirit.