“The closer the likeness … the more virulent the hatred.”

BY MARIA POPOVA

“Hate, in the long run, is about as nourishing as cyanide,” Kurt Vonnegut admonished in his magnificent Fredonia commencement address. But when the run is generations long — when hate lodges itself in the soul of its carrier and becomes part of the spiritual DNA that propagates the species — it becomes more toxic than anything human beings can synthesize.

Decades before Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. asserted that “along the way of life, someone must have sense enough and morality enough to cut off the chain of hate,” a forgotten woman offered an incisive perspective on hate’s paradoxical quality to both repel and bind with its magnetic chain stretched across time.

Millicent Todd Bingham (February 5, 1880–December 1, 1968) was the daughter of astronomer David Todd and writer Mabel Loomis Todd, who penned the first popular science book on eclipses and who, through a maelstrom of complicated family dynamics and antagonisms, ended up as the steward of Emily Dickinson’s body of work. For two decades, Mabel had been the lover of the poet’s brother, Austin. Her invasion of the lives of the Dickinsons caused a rupture from which the family never recovered. When she edited the first volumes of Emily Dickinson’s letters and poems to enter the world, Mabel didn’t hesitate to exercise her position of literary power in advancing her personal agenda — to excise from the record her lover’s wife, Susan Dickinson.

Before marrying Austin Dickinson, Susan had been young Emily Dickinson’s first great love and would remain her greatest for the rest of the poet’s life. Some of Dickinson’s best known and most electrifying poems were dedicated to Susan, her “only woman in the world”; some of her most passionate letters written to her. Throughout Dickinson’s life, Susan would be her most important reader — and often editor — making Todd’s manipulative mission of excision all the more cruel, and all the more difficult, for Susan animated the vast majority of Dickinson’s writing.

Emily Dickinson’s legacy would become the front onto which the war between Austin Dickinson’s wife and his lover would be fought. The hatred that Susan and Mabel brought to the feud would survive them both, finding new life in their daughters: Martha Dickinson and Millicent Todd.

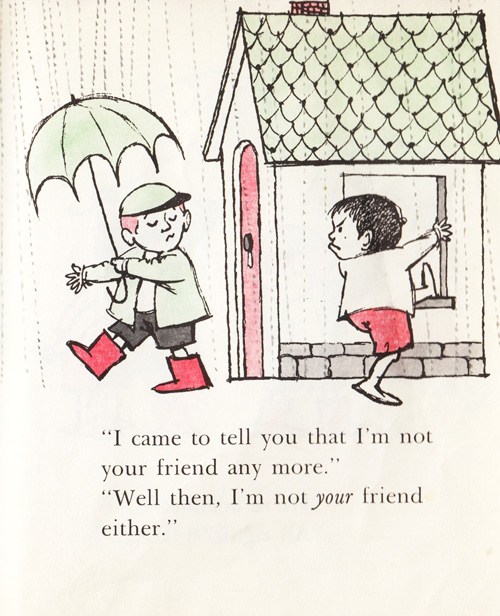

Illustration by Maurice Sendak from Let’s Be Enemies by Janice May Udry

As Millicent neared sixty, she reflected on the paradoxical psychological mechanism undergirding such enduring transgenerational hate in an arresting piece cited in Lyndall Gordon’s Lives Like Loaded Guns: Emily Dickinson and Her Family’s Feuds (public library) — the most nuanced, insightful, and beautifully written of what has become a self-standing canon of Dickinson biographies.

In a passage that applies with equally perceptive precision to the durational hatreds between human factions as varied as sports teams and political parties, social groups and nations, Millicent writes:

Hatred implies similarity, that is, lasting hatred does. The kind of hatred that implies incentive enough to enable it to last a lifetime — strength enough to propel it beyond the grave and loop it in the hearts of a succeeding generation. The kind of congenital hatred means a feud — and a feud does not flourish among aliens … The most virulent kind seems to get its start in stealing of affections, and affections usually do not exist between aliens … Real hate is focussed … and focussing on a negative purpose may be carried out with as much or more determination. It’s not iniquity which the hater hates; he’s hating during an interval while waiting till the opportunity comes for vengeance. This waiting through a life-time does not destroy the carrier; on the contrary it seems to add the vitality to prolong life. The emotion, the hatred, keeps the hater alive and vigorous. The affection which starts a feud may be between aliens, but the hates it engenders does not continue unless between kindred souls and the closer the likeness perhaps, the more virulent the hatred.

Complement with a Zen master’s strategy for handling hate, then revisit the mightiest antidote we have to this most virulent of hatreds — the Ancient Greek notion of agape.