“The Little Prince will shine upon children with a sidewise gleam. It will strike them in some place that is not the mind and glow there until the time comes for them to comprehend it.”

Although Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (June 29, 1900–July 31, 1944) only wrote one children’s book in his lifetime, it is among the most beloved of all time, one of those rare gems with most timeless philosophy for grown-ups. But what few realize is that Saint-Exupéry, a commercial pilot who never mastered English and penned his masterwork in French, wrote The Little Prince (public library) not in Paris but in New York City and Long Island, where he arrived in 1940 after the Nazi invasion of France.

In April of 1943, shortly after the book came out, 43-year-old Saint-Exupéry shoved his Little Prince manuscripts and drawings in a brown paper bag, handing it to his friend Silvia Hamilton — “I’d like to give you something splendid,” he told her, “but this is all I have.” — and departed for Algiers as a military pilot with the Free French Air Force. He was eight years over the age limit for pilots in such squadrons, so he petitioned relentlessly for exemption until it was finally granted by General Dwight Eisenhower. On July 31, 1944, he left on a reconnaissance mission, never to return. He was 44 years old when he perished — a biographical detail that lends eerie poignancy to the fact that, perched atop his little planet, the Little Prince watched the sun set exactly 44 times.

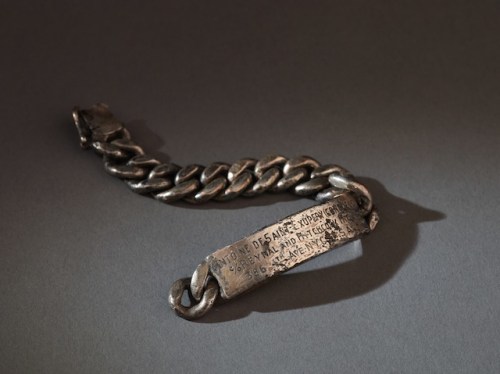

Parts of his plane were found years later. A fisherman near Marseilles caught Saint-Exupéry’s silver bracelet in his net. Along with the author’s name, that of his wife, and his American publisher’s address, the inscription read “NYC USA.”

The Little Prince wasn’t published in the author’s native France until two years after his death. Even in America, it was only a moderate success initially — it only stayed on The New York Times bestseller list for two weeks, compared to twenty for Saint-Exupéry’s aviation memoir, Wind, Sand and Stars, perhaps because it occupied that odd, uncategorizable neverland between a children’s story and philosophical fable for adults. And yet precisely therein lies the book’s timeless magic. Today, it has been translated into more than 260 languages and dialects, and it lands in millions of hands, little and big, each year.

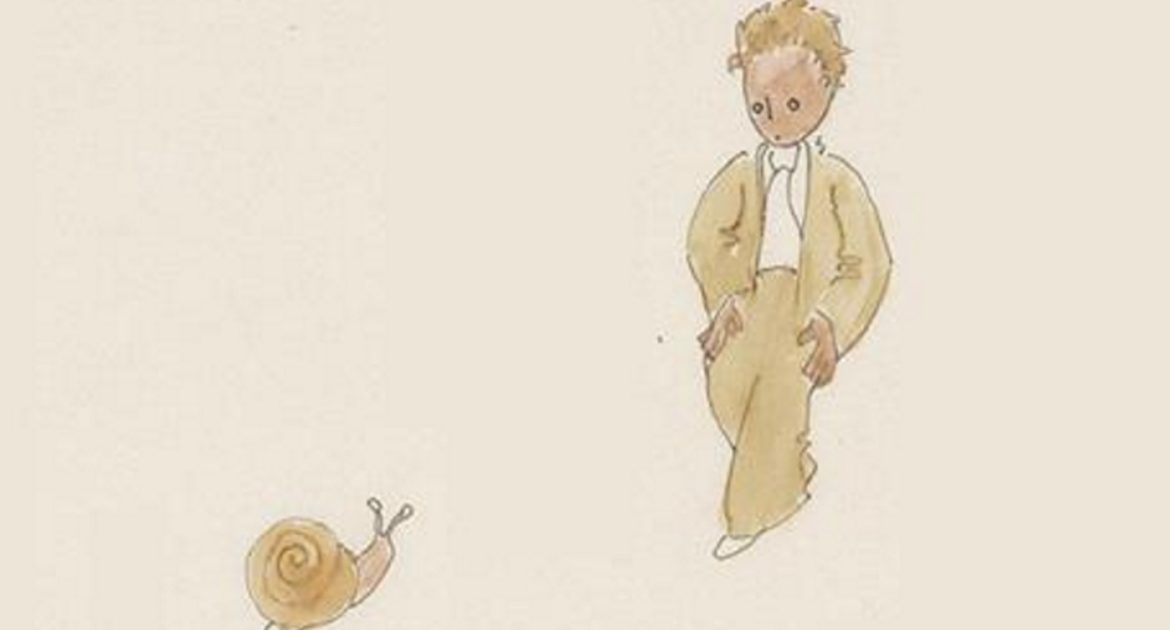

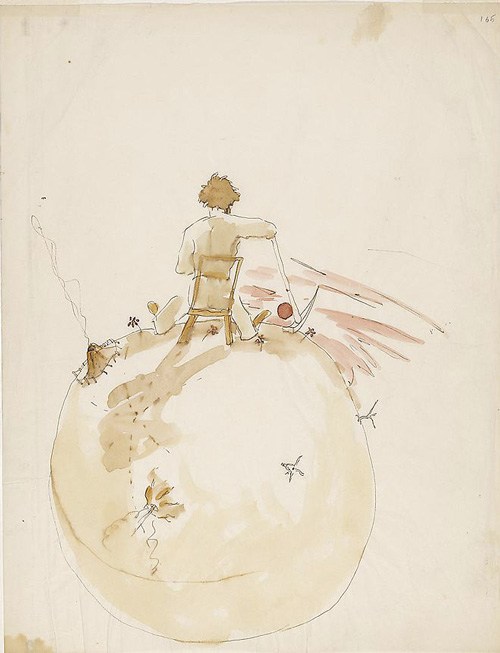

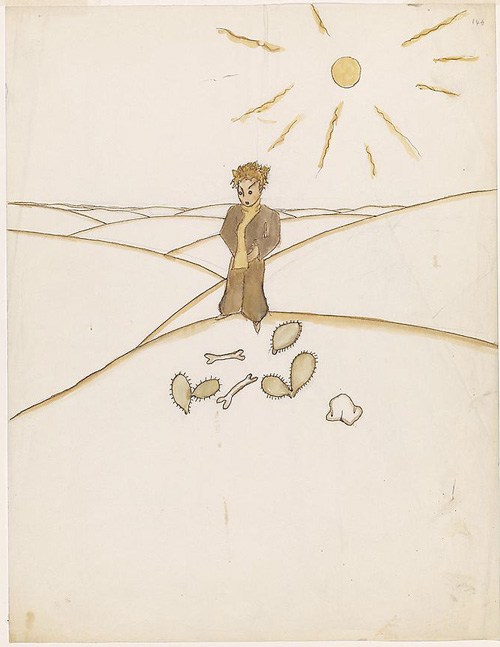

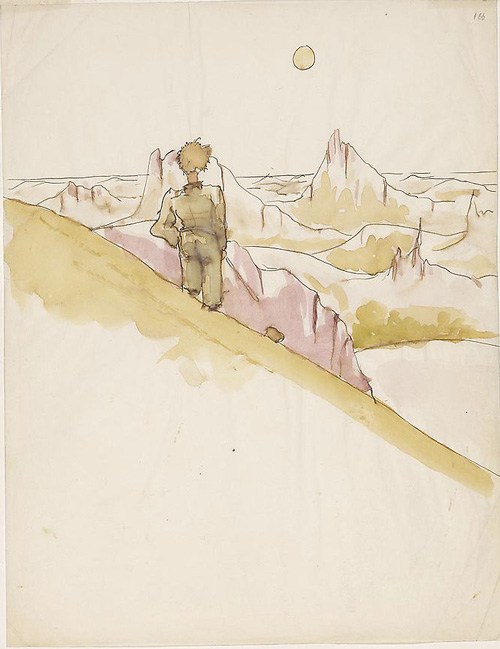

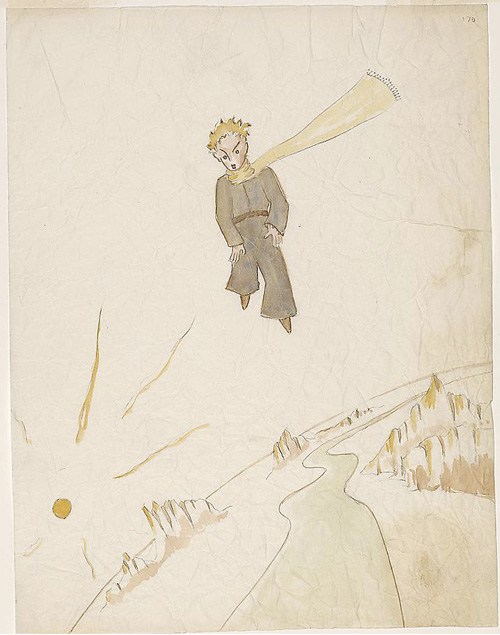

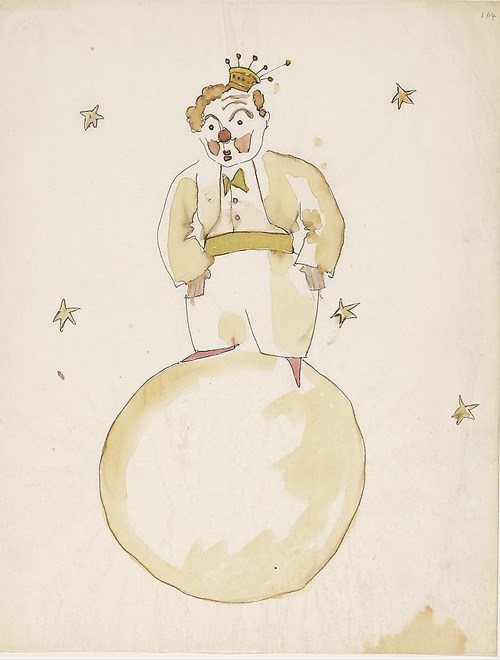

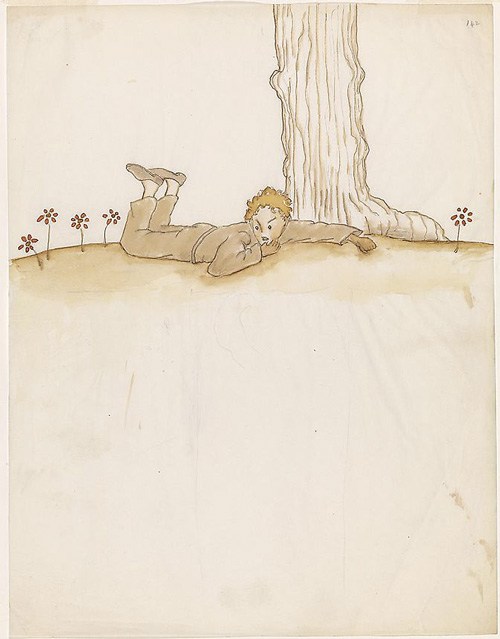

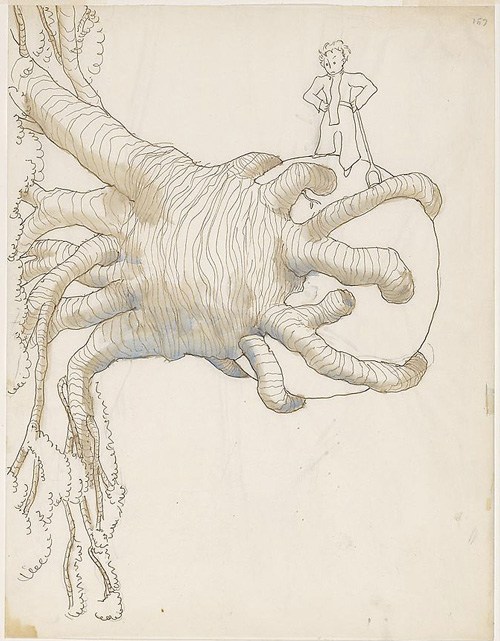

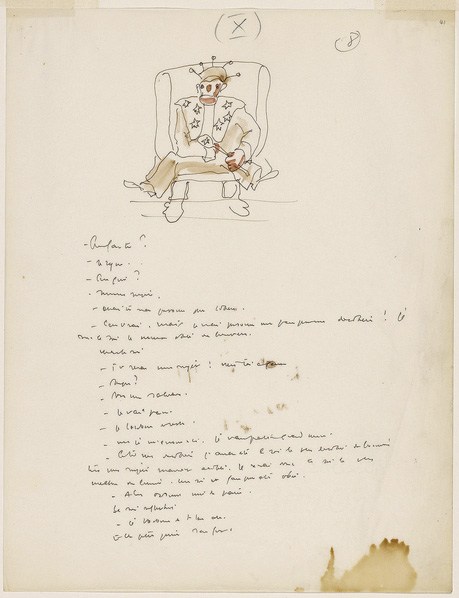

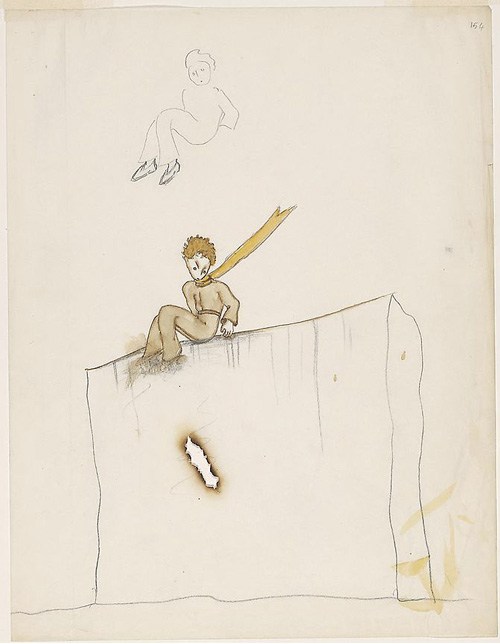

In 1968, The Morgan Library in New York — home to such treasures as the life of Rumi in rare Islamic paintings and the illustrated to-do lists of famous artists — acquired the original manuscripts. Now, a new Morgan exhibition explores Saint-Exupéry’s creative process through the writings that he excluded from the final version — the Morgan manuscript contains 30,000 words, nearly double those in the published book — and his little-known original watercolors, among other biographical ephemera. Indeed, what made Saint-Exupéry such a singular artist of the imagination was that he ranked among those rare writers who also illustrated their own works — celebrated creators like Maurice Sendak, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Maira Kalman — with text and image informing and enriching one another.

What makes these drawings most extraordinary is that they at once embody and counter Saint-Exupéry’s most memorable line — “What is essential is invisible to the eye.” — by seeking to make visible, even seen, the creative craftsmanship of a man who long after his death continues to move generations with his tender tale about the meaning of life.

![MA 2592.32 Saint-ExupeÌry, Antoine de, 1900-1944. Le petit prince et la main du pilote tenant un marteau [New York, 1942]](http://us.abrozzi.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/thelittleprince_morgan12.jpg)

Saint-Exupéry was among the many famous writers with odd habits and questionable sleep regimens: He wrote well into the night and had no scruples about calling up a friend at 2 A.M. to read a passage aloud; he carried a cup of coffee or tea with him at all times and almost always had a cigarette hanging out of his mouth. Unsurprisingly, those habits are imprinted — quote literally — on his work, as in the coffee stain on this early Little Prince manuscript page:

One of the drawings even has a cigarette burn:

Also included in the exhibition, envisioned by Morgan Library curator Christine Nelson, are the last photographs taken of Saint-Exupéry, captured by LIFE photojournalist John Phillips, whose account of a conversation with Saint-Exupéry is our only record of the inspiration for the book:

«When I asked Saint-Ex how the Little Prince had entered his life, he told me that one day he looked down on what he thought was a blank sheet and saw a small childlike figure. “I asked him who he was, ” Saint-Ex said. “I’m the Little Prince,” was the reply.

Indeed, Saint-Exupéry’s beloved character evolved largely in the margins of his letters and notebooks. In a 1940 missive to a friend, he doodled a character with thinning hair, much like his own, wearing a bow-tie. He gave a similar drawing to Elizabeth Reynal, a French-speaking friend in New York, who eventually convinced him to weave his character into a children’s story.

One of the loveliest meta-materials in the exhibit is a 1943 review of The Little Prince by P.L. Travers for the New York Herald Tribune, echoing Tolkien’s conviction that there is no such thing as writing “for children” and articulating the profound, timeless appeal of the book with exquisite sensitivity:

«Children quite naturally see with the heart, the essential is clearly visible to them. The little fox will move them simply by being a fox. They will not need his secret until they have forgotten it and have to find it again. I think, therefore, that The Little Prince will shine upon children with a sidewise gleam. It will strike them in some place that is not the mind and glow there until the time comes for them to comprehend it. Yet even in saying this I am conscious of drawing a line between grown-ups and children. . . . And I do not believe that line exists.

Saint-Exupéry’s original full-color drawings are included in the 70th anniversary boxed set edition of The Little Prince. The Morgan Library’s The Little Prince: A New York Story is on view through April 27, 2014.