“We must gain victory, not by assaulting the walls, but by accepting them.”

BY MARIA POPOVA

As far as vintage finds go, they hardly get more fortuitous than You Can Master Life (public library) — a marvelous 1934 compendium of sort-of-philosophical, sort-of-self-helpy, at times charmingly dated, other times refreshingly timeless advice on cultivating “the power to think, to create, to influence and be influenced by others, and to love,” in the spirit of the 1949 gem How To Avoid Work.

Though written by a Christian pastor named James Gordon Gilkey and thus a little too God-heavy for these corners of the internet, the slim volume shares a good amount in common with Alain de Botton’s modern-day advocacy of the secular sermon. Take, for instance, Gilkey’s advice in a chapter titled “Breaking the Grip of Worry.” He cites a “Worry Table” created by one of the era’s humorists — most likely Mark Twain, who is often quoted, though never with a specific source, as having said, “I’ve had a lot of worries in my life, most of which never happened.” The table was designed to distinguish between justified and unjustified worries:

On studying his chronic fears this man found they fell into five fairly distinct classifications:

Worries about disasters which, as later events proved, never happened. About 40% of my anxieties.

Worries about decisions I had made in the past, decisions about which I could now of course do nothing. About 30% of my anxieties.

Worries about possible sickness and a possible nervous breakdown, neither of which materialized. About 12% of my worries.

Worries about my children and my friends, worries arising from the fact I forgot these people have an ordinary amount of common sense. About 10% of my worries.

Worries that have a real foundation. Possibly 8% of the total.

Gilkey then prescribes:

What, of this man, is the first step in the conquest of anxiety? It is to limit his worrying to the few perils in his fifth group. This simple act will eliminate 92% of his fears. Or, to figure the matter differently, it will leave him free from worry 92% of the time.

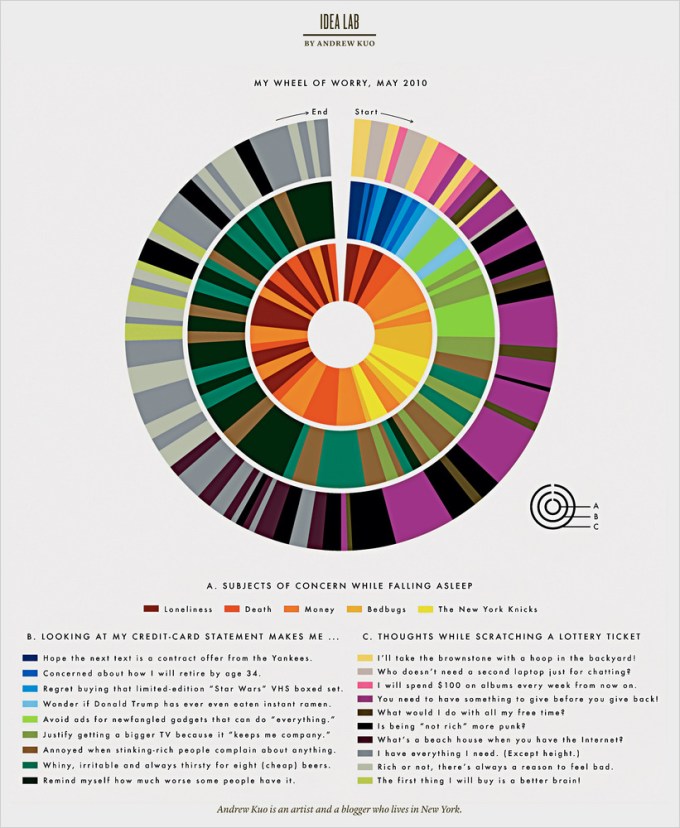

The concept of the worry table is strikingly reminiscent — and, one has to wonder, might have inspired — artist Andrew Kuo’s elaborate 2008 graphic My Wheel of Worry:

(Of course, F. Scott Fitzgerald intuited the basic premise of the table when he sent his daughter Scottie an itemized list of the things in life to worry and not worry about.)

In a later chapter, titled “Doing One’s Work Under Difficulties,” Gilkey offers some related advice which, on the one hand, bears that wise Buddhist-like mindset of living with sheer awareness but, on the other, makes a questionable case against introspection and the enormous enrichment of “living the questions”:

We should make ourselves stop trying to explain our own difficulties. Our first impulse is to try to account for them, figure out why what has happened did happen. Sometimes such an effort is beneficial: more often it is distinctly harmful. It leads to introspection, self-pity, and vain regret; and almost invariably it creates within us a dangerous mood of confusion and despair. Many of life’s hard situations cannot be explained. They can only be endured, mastered, and gradually forgotten. Once we learn this truth, once we resolve to use all our energies managing life rather than trying to explain life, we take the first and most obvious step toward significant accomplishment.

In the following chapter, “Learning to Adjust,” Gilkey revisits the subject through the lens of aging:

Only as we yield to the inexorable, only as we accept the situations which we find ourselves powerless to change, can we free ourselves from fatal inward tensions, and acquire that inward quietness amid which we can seek — and usually find — ways by which our limitations can be made at least partially endurable.

[…]

Why is [this] so difficult for most people? because most of us were told in childhood that the way to conquer a difficulty is to fight it and demolish it. That theory is, of course, the one that should be taught to young people. Many of the difficulties we encounter in youth are not permanent; and the combination of a heroic courage, a resolute will, and a tireless persistence will often — probably usually — break them down. But in later years the essential elements in the situation change. We find in our little world prison-walls which no amount of battering will demolish. Within those walls we must spend our day — spend them happily, or resentfully. Under these new circumstances we must deliberately reverse our youthful technique. We must gain victory, not by assaulting the walls, but by accepting them. Only when this surrender is made can we assure ourselves of inward quietness, and locate the net step on the road to ultimate victory.

Complement You Can Master Life with a contemporary counterpart of sorts, the wonderful and wonderfully useful How To Stay Sane, then wash down with a verse-by-verse neuropsychology reading of Bobby McFerrin’s “Don’t Worry, Be Happy.”