“Grief, when it comes, is nothing like we expect it to be.”

BY MARIA POPOVA

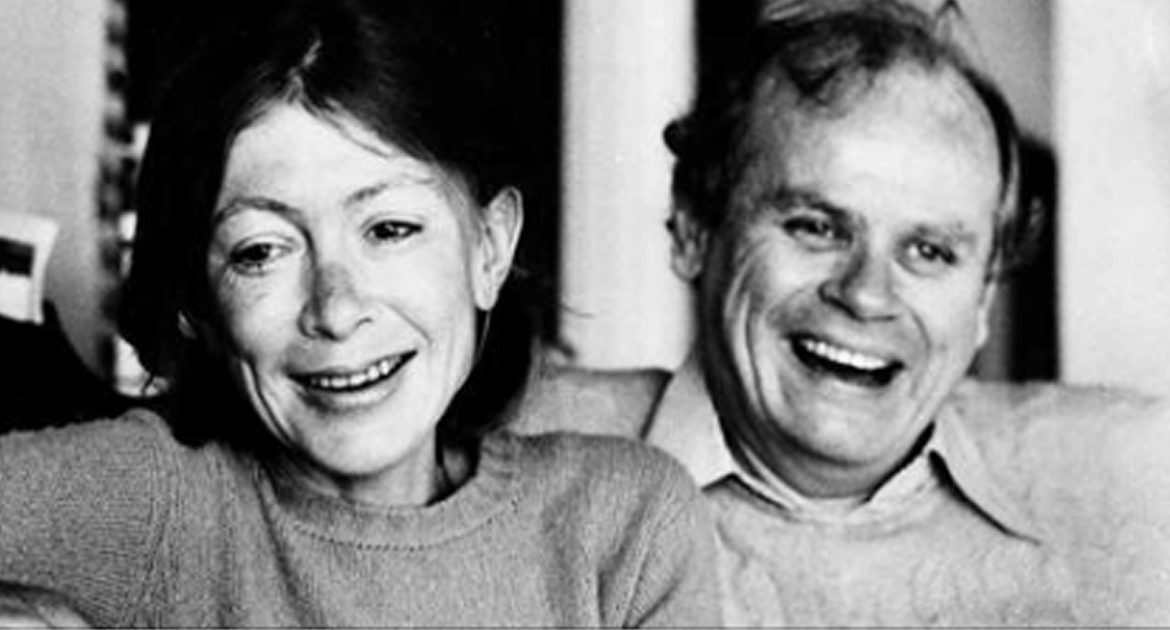

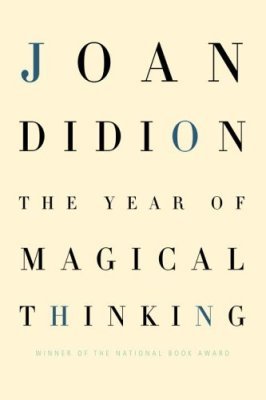

“To lament that we shall not be alive a hundred years hence, is the same folly as to be sorry we were not alive a hundred years ago,” Montaigne wrote in his 16th-century essay on death and the art of living. And yet we continue to grapple with the paradox of our mortality. But arguably our most formidable and intense confrontation with nonexistence comes when we lose loved ones. In The Year of Magical Thinking (public library), her harrowing record of the year following the death of her husband of four decades, John Gregory Dunne, Joan Didion, born on December 5, 1934, offers a soul-stirring meditation on grief in all its unimaginable dimensions:

Grief, when it comes, is nothing like we expect it to be. … Grief has no distance. Grief comes in waves, paroxysms, sudden apprehensions that weaken the knees and blind the eyes and obliterate the dailiness of life. Virtually everyone who has ever experienced grief mentions this phenomenon of “waves.”

And then she dives into the rippling depths of it:

Grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it. We anticipate (we know) that someone close to us could die, but we do not look beyond the few days or weeks that immediately follow such an imagined death. We misconstrue the nature of even those few days or weeks. We might expect if the death is sudden to feel shock. We do not expect the shock to be obliterative, dislocating to both body and mind. We might expect that we will be prostrate, inconsolable, crazy with loss. We do not expect to be literally crazy, cool customers who believe that their husband is about to return and need his shoes. In the version of grief we imagine, the model will be “healing.” A certain forward movement will prevail. The worst days will be the earliest days. We imagine that the moment to most severely test us will be the funeral, after which this hypothetical healing will take place. When we anticipate the funeral we wonder about failing to “get through it,” rise to the occasion, exhibit the “strength” that invariably gets mentioned as the correct response to death. We anticipate needing to steel ourselves the for the moment: will I be able to greet people, will I be able to leave the scene, will I be able even to get dressed that day? We have no way of knowing that this will not be the issue. We have no way of knowing that the funeral itself will be anodyne, a kind of narcotic regression in which we are wrapped in the care of others and the gravity and meaning of the occasion. Nor can we know ahead of the fact (and here lies the heart of the difference between grief as we imagine it and grief as it is) the unending absence that follows, the void, the very opposite of meaning, the relentless succession of moments during which we will confront the experience of meaninglessness itself.

The Year of Magical Thinking is a superb read in its entirety — enormously difficult, but the kind that stays with you for a lifetime. Complement it with Didion on self-respect, keeping a notebook, and the motives for writing.