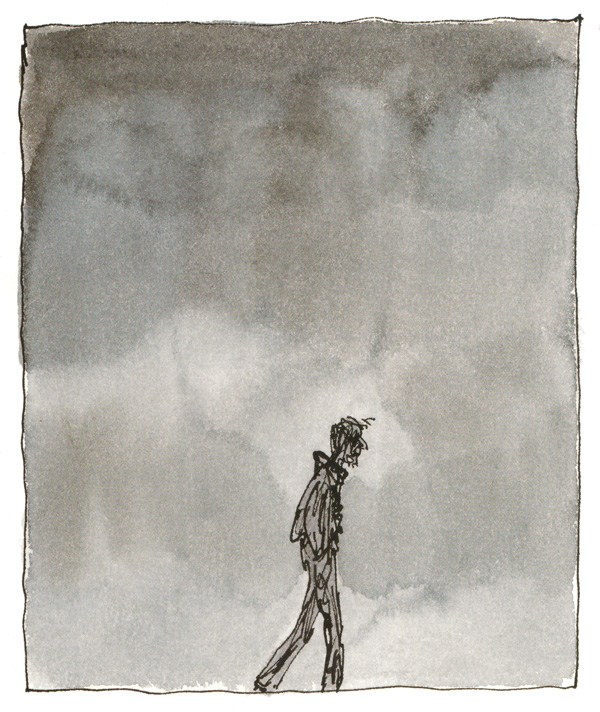

“Sometimes I’m sad and I don’t know why. It’s just a cloud that comes along and covers me up.”

BY MARIA POPOVA

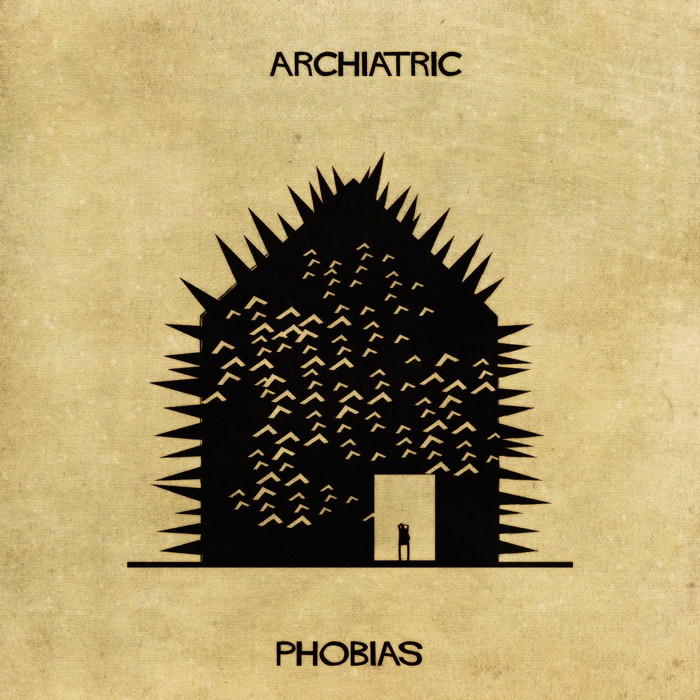

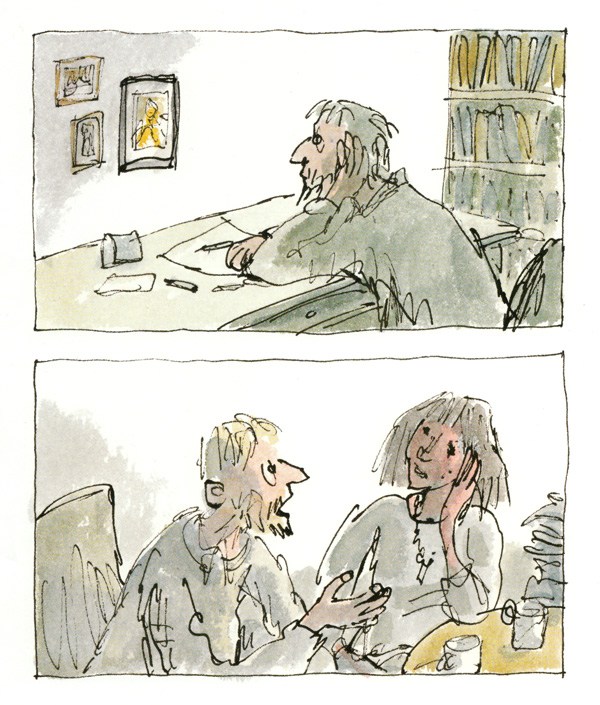

“Grief, when it comes, is nothing like we expect it to be,” Joan Didion wrote after losing the love of her life. “The people we most love do become a physical part of us,” Meghan O’Rourke observed in her magnificent memoir of loss, “ingrained in our synapses, in the pathways where memories are created.” Those wildly unexpected dimensions of grief and the synaptic traces of love are what celebrated British children’s book writer and poet Michael Rosen confronted when his eighteen-year-old son Eddie died suddenly of meningitis. Never-ending though the process of mourning may be, Rosen set out to exorcise its hardest edges and subtlest shapes five years later in Michael Rosen’s Sad Book (public library) — an immensely moving addition to the finest children’s books about loss, illustrated by none other than the great Quentin Blake.

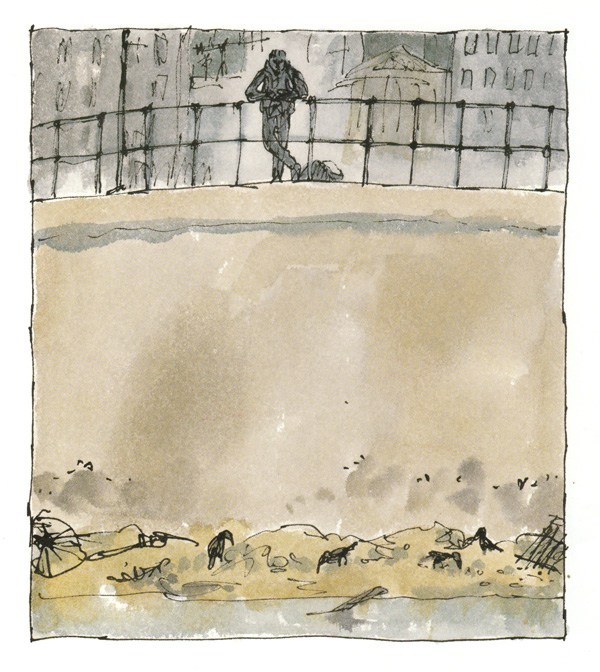

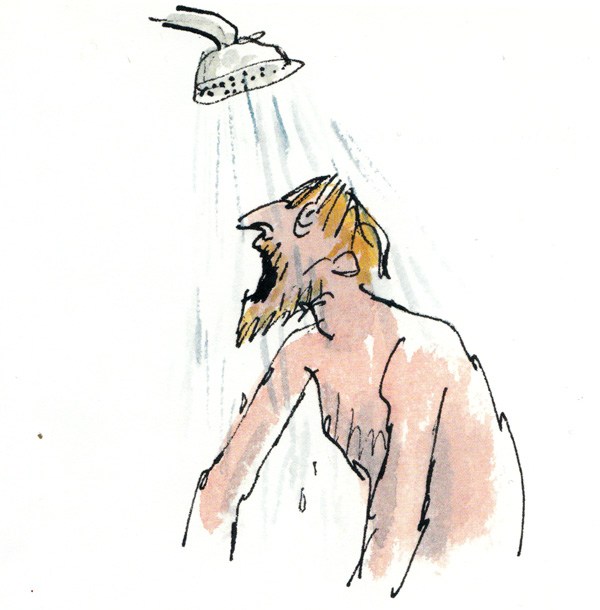

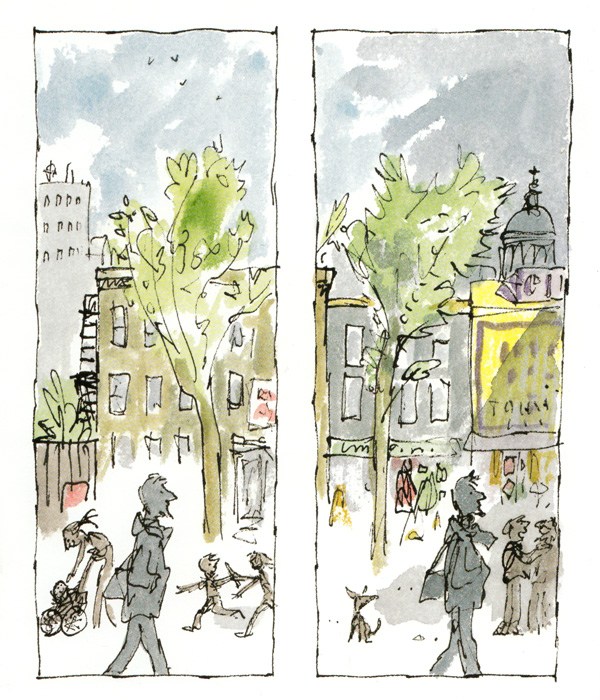

With extraordinary emotional elegance, Rosen welcomes the layers of grief, each unmasking a different shade of sadness — sadness that sneaks up on you mid-stride in the street; sadness that lurks as a backdrop to the happiest of moments; sadness that wraps around you like a shawl you don’t take off even in the shower.

What emerges is a breathtaking bow before the central paradox of the human experience — the awareness that the heart’s enormous capacity for love is matched with an equal capacity for pain, and yet we love anyway and somehow find fragments of that love even amid the ruins of loss.

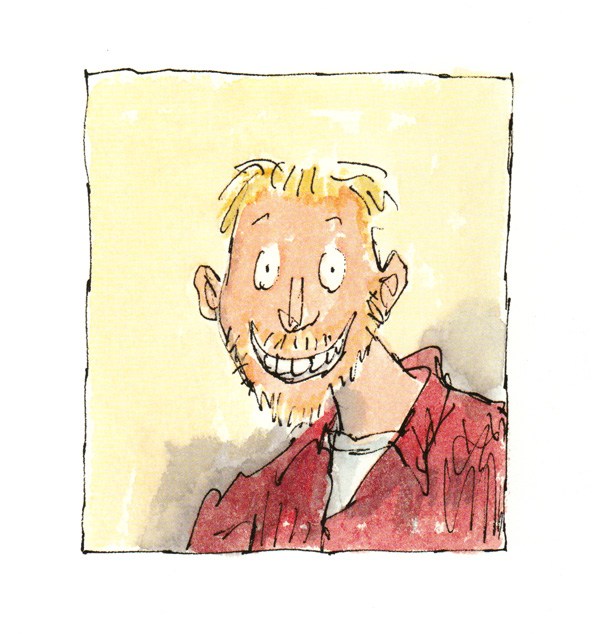

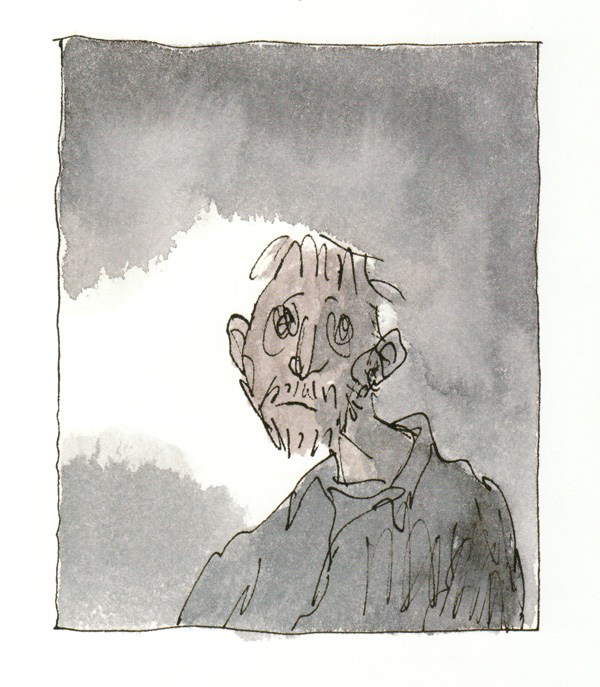

This is me being sad.

Maybe you think I’m happy in this picture.

Really I’m sad but pretending I’m happy.

I’m doing this because I think people won’t like me if I look sad.

Sometimes sad is very big.

It’s everywhere. All over me.

Then I look like this.

And there’s nothing I can do about it.

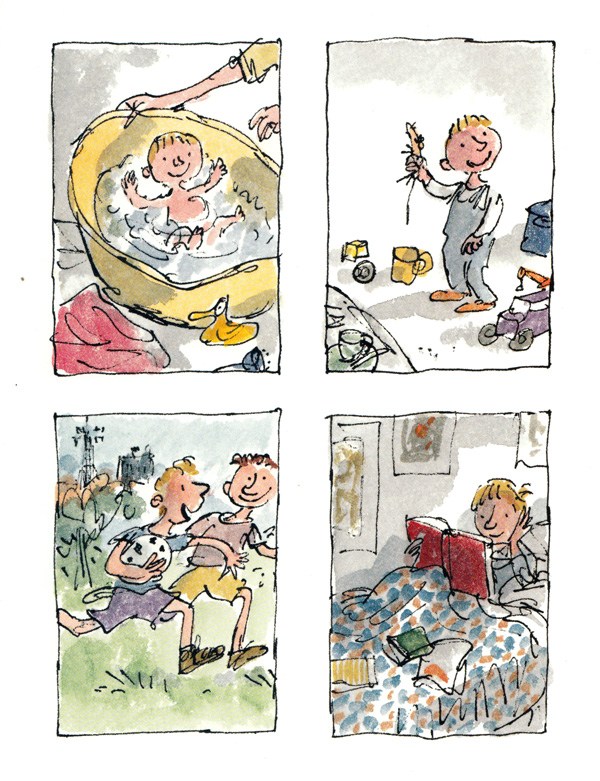

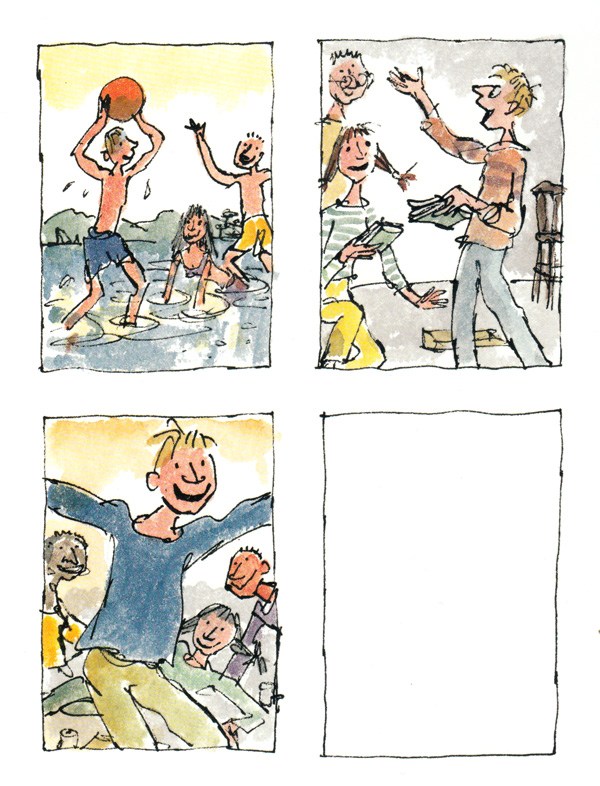

What makes me most sad is when I think about my son Eddie. I loved him very, very much but he died anyway.

With exquisite nuance, Rosen captures the contradictory feelings undergirding mourning — affection and anger, self-conscious introspection and longing for communion — and the way loss lodges itself in the psyche so that the vestiges of a particular loss always awaken the sadness of the all loss, that perennial heartbreak of beholding the absurdity of our longing for permanence in a universe of constant change.

Sometimes this makes me really angry.

I say to myself, “How dare he go and die like that?

How dare he make me sad?”

Eddie doesn’t say anything,

because he’s not here anymore.

Sometimes I want to talk about all this to someone.

Like my mum. But she’s not here anymore, either. So I can’t.

I find someone else. And I tell them all about it.

Sometimes I don’t want to talk about it.

Not to anyone. No one at all.

I just want to think about it on my own.

Because it’s mine. And no one else’s.

But what makes the story most singular and rewarding is that it refuses to indulge the cultural cliché of cushioning tragedy with the promise of a silver lining. It is redemptive not in manufacturing redemption but in being true to the human experience — intensely, beautifully, tragically true.

Sometimes because I’m sad I do crazy things — like shouting in the shower…

Sometimes I’m sad and I don’t know why.

It’s just a cloud that comes along and covers me up.

It’s not because Eddie’s gone.

It’s not because my mum’s gone. It’s just because.

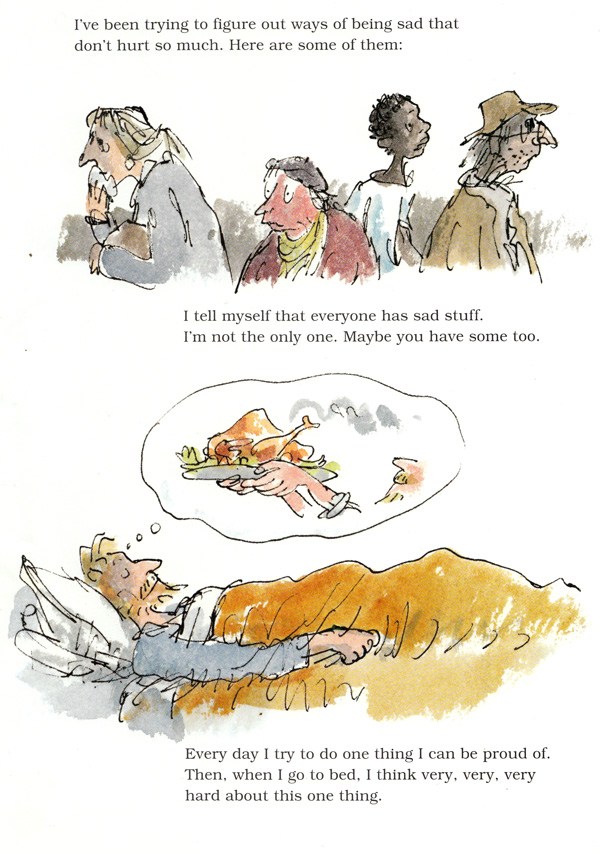

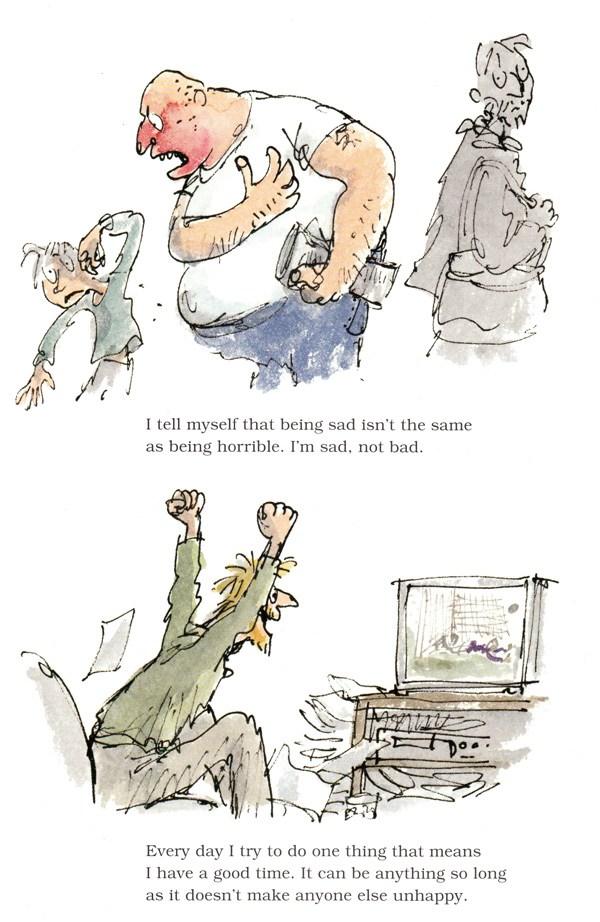

Blake, who has previously illustrated Sylvia Plath’s little-known children’s book and many of Roald Dahl’s stories, brings his unmistakably expressive sensibility to the book, here and there concretizing Rosen’s abstract words into visual vignettes that make you wonder what losses of his own he is holding in the mind’s eye as he draws.

Where is sad?

Sad is everywhere.

It comes along and finds you.

When is sad?

Sad is anytime.

It comes along and finds you.

Who is sad?

Sad is anyone.

It comes along and finds you.

Complement the absolutely breath-stopping Michael Rosen’s Sad Book with Oliver Jeffers’s The Heart and the Bottle and the Japanese masterpiece Little Tree, then revisit Joan Didion on grief.