“To approach someone else convincingly you must do so with open arms and head held high, and your arms can’t be open unless your head is high,” the Lebanese-born French writer Amin Maalouf wrote in his timeless, increasingly timely reflection on how to disagree. It is in times as divisive as ours and as sundered by conflicting perspectives that the mastery of such intelligent, kind-hearted, and considered disagreement emerges as a supreme art of living. To respond in a reactive culture, to marry firm moral conviction with a spirit of goodwill and the porousness necessary for appraising other perspectives in order to evolve one’s own, is a Herculean feat of character.

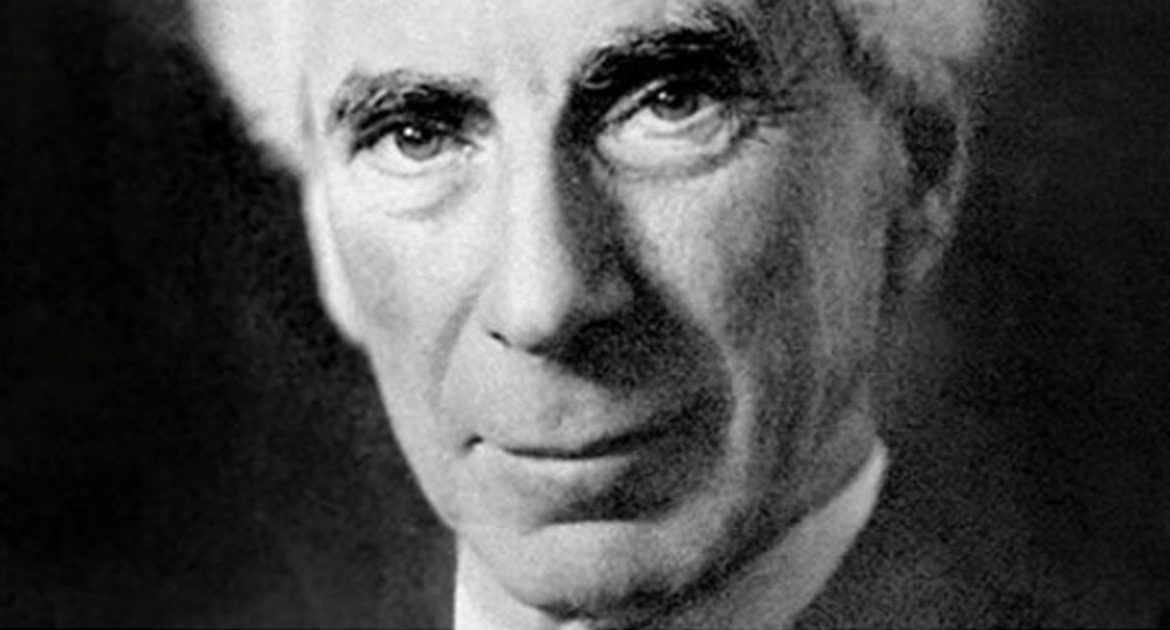

And yet there are instances in which it is unsound to engage with another whose values are so antithetical to one’s own that the collision is bound to shatter one’s sanity rather than build common ground. To recognize those rare instances and choose to stand down is an act of moral courage rather than moral weakness, and no one has articulated that difficult courage with more intellectual elegance and moral grace than the great English philosopher Bertrand Russell (May 18, 1872–February 2, 1970) — a formidable intellect animated by an extraordinary generosity of spirit, awarded the Nobel Prize for “his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought.”

In January of 1962, Russell received a series of letters from an unlikely correspondent — Sir Oswald Mosley, who had founded the British Union of Fascists thirty years earlier. Mosley was inviting — or, rather, provoking — Russell to engage in a debate, in which he could persuade the moral philosopher of the merits of fascism. Russell’s considered and morally unflinching response, included in Ronald Clark’s excellent biography The Life of Bertrand Russell (public library), stands as a manifesto for the right not to engage in a debate with a counterpart so morally misaligned with oneself as to guarantee not only the self-defeating futility of such engagement but its detrimental cost to one’s own sanity.

Shortly before his 90th birthday, Russell writes:

Dear Sir Oswald,

Thank you for your letter and for your enclosures. I have given some thought to our recent correspondence. It is always difficult to decide on how to respond to people whose ethos is so alien and, in fact, repellent to one’s own. It is not that I take exception to the general points made by you but that every ounce of my energy has been devoted to an active opposition to cruel bigotry, compulsive violence, and the sadistic persecution which has characterised the philosophy and practice of fascism.

I feel obliged to say that the emotional universes we inhabit are so distinct, and in deepest ways opposed, that nothing fruitful or sincere could ever emerge from association between us.

I should like you to understand the intensity of this conviction on my part. It is not out of any attempt to be rude that I say this but because of all that I value in human experience and human achievement.

Yours sincerely,

Bertrand Russell

The Life of Bertrand Russell remains an invaluable portrait of one of the greatest intellects and largest spirits our civilization has produced. Complement this particular fragment with Blaise Pascal on how to change minds, Daniel Dennett on how to criticize with kindness, and Susan Sontag on the three steps to refuting any argument, then revisit Russell on freedom of thought, what “the good life” really means, why “fruitful monotony” is essential for happiness, the nature of time, and the four motives driving all human behavior.