“If your project has real substance, ultimately the money will follow you like a common cur in the street with its tail between its legs.”

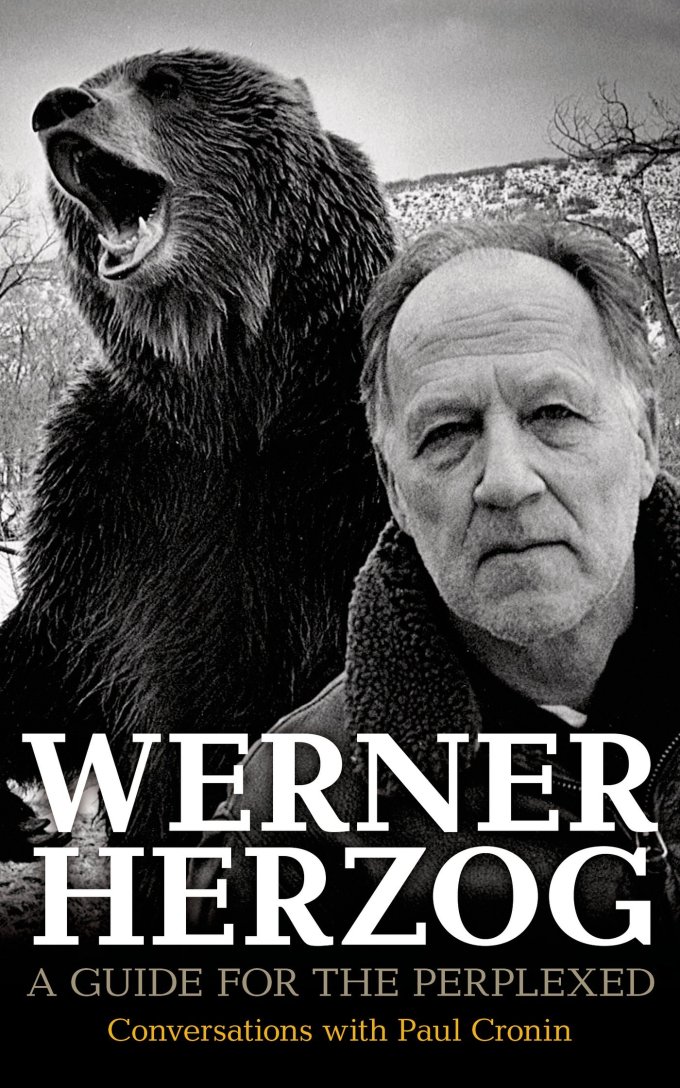

Werner Herzog is celebrated as one of the most influential and innovative filmmakers of our time, but his ascent to acclaim was far from a straight trajectory from privilege to power. Abandoned by his father at an early age, Herzog survived a WWII bombing that demolished the house next door to his childhood home and was raised by a single mother in near-poverty. He found his calling in filmmaking after reading an encyclopedia entry on the subject as a teenager and took a job as a welder in a steel factory in his late teens to fund his first films. These building blocks of his character — tenacity, self-reliance, imaginative curiosity — shine with blinding brilliance in the richest and most revealing of Herzog’s interviews. Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed (public library) — not to be confused with E.F. Schumacher’s excellent 1978 philosophy book of the same title — presents the director’s extensive, wide-ranging conversation with writer and filmmaker Paul Cronin. His answers are unfiltered and to-the-point, often poignant but always unsentimental, not rude but refusing to infest the garden of honest human communication with the Victorian-seeded, American-sprouted weed of pointless politeness.

Herzog’s insights coalesce into a kind of manifesto for following one’s particular calling, a form of intelligent, irreverent self-help for the modern creative spirit — indeed, even though Herzog is a humanist fully detached from religion, there is a strong spiritual undertone to his wisdom, rooted in what Cronin calls “unadulterated intuition” and spanning everything from what it really means to find your purpose and do what you love to the psychology and practicalities of worrying less about money to the art of living with presence in an age of productivity. As Cronin points out in the introduction, Herzog’s thoughts collected in the book are “a decades-long outpouring, a response to the clarion call, to the fervent requests for guidance.”

And yet in many ways, A Guide for the Perplexed could well have been titled A Guide to the Perplexed, for Herzog is as much a product of his “cumulative humiliations and defeats,” as he himself phrases it, as of his own “chronic perplexity,” to borrow E.B. White’s unforgettable term — Herzog possesses that rare, paradoxical combination of absolute clarity of conviction and wholehearted willingness to inhabit his own inner contradictions, to pursue life’s open-endedness with equal parts focus of vision and nimbleness of navigation.

A certain self-reliance that permeates his films and his mind, a refusal to let the fear of failure inhibit trying — a sensibility the voiceover in the final scene of Herzog’s The Unprecedented Defence of the Fortress Deutschkreuz captures perfectly: “Even a defeat is better than nothing at all.” He tells Cronin:

There is nothing wrong with hardships and obstacles, but everything wrong with not trying.

Herzog reflects on failure as a prerequisite for creative mastery:

The bad films have taught me most about filmmaking. Seek out the negative definition. Sit in front of a film and ask yourself, “Given the chance, is this how I would do it?” It’s a never-ending educational experience, a way of discovering in which direction you need to take your own work and ideas.

He takes this notion of self-reliance — as he does most things he believes — to an almost religious degree:

I did as much as possible myself; it was an article of faith, a matter of simple human decency to do the dirty work as long as I could… Three things — a phone, computer and car — are all you need to produce films. Even today I still do most things myself. Although at times it would be good if I had more support, I would rather put the money up on the screen instead of adding people to the payroll.

Indeed, having grown up without money and earned every penny himself, Herzog considers this self-reliance closely intertwined with the question of financial struggle — a circumstance he always refused to mistake for a fatal roadblock to the creative drive. His wisdom on the subject extends beyond film and applies just as perceptively to almost any field of endeavor in today’s creative landscape:

The best advice I can offer to those heading into the world of film is not to wait for the system to finance your projects and for others to decide your fate. If you can’t afford to make a million-dollar film, raise $10,000 and produce it yourself. That’s all you need to make a feature film these days. Beware of useless, bottom-rung secretarial jobs in film-production companies. Instead, so long as you are able-bodied, head out to where the real world is. Roll up your sleeves and work as a bouncer in a sex club or a warden in a lunatic asylum or a machine operator in a slaughterhouse. Drive a taxi for six months and you’ll have enough money to make a film. Walk on foot, learn languages and a craft or trade that has nothing to do with cinema. Filmmaking — like great literature — must have experience of life at its foundation. Read Conrad or Hemingway and you can tell how much real life is in those books. A lot of what you see in my films isn’t invention; it’s very much life itself, my own life. If you have an image in your head, hold on to it because — as remote as it might seem — at some point you might be able to use it in a film. I have always sought to transform my own experiences and fantasies into cinema.

He later revisits the subject even more pointedly:

A natural component of filmmaking is the struggle to find money. It has been an uphill battle my entire working life… If you want to make a film, go make it. I can’t tell you the number of times I have started shooting a film knowing I didn’t have the money to finish it. I meet people everywhere who complain about money; it’s the ingrained nature of too many filmmakers. But it should be clear to everyone that money has always had certain explicit qualities: it’s stupid and cowardly, slow and unimaginative. The circumstances of funding never just appear; you have to create them yourself, then manipulate them for your own ends. This is the very nature and daily toil of filmmaking. If your project has real substance, ultimately the money will follow you like a common cur in the street with its tail between its legs. There is a German proverb: “Der Teufel scheisst immer auf den grössten Haufen” [“The Devil always shits on the biggest heap”]. So start heaping and have faith. Every time you make a film you should be prepared to descend into Hell and wrestle it from the claws of the Devil himself. Prepare yourself: there is never a day without a sucker punch. At the same time, be pragmatic and learn how to develop an understanding of when to abandon an idea. Follow your dreams no matter what, but reconsider if they can’t be realized in certain situations. A project can become a cul-de-sac and your life might slip through your fingers in pursuit of something that can never be realized. Know when to walk away.

This question of money parlays into what’s perhaps Herzog’s most urgent and piercing point — a testament to the idea that anything worthwhile takes a long time:

Perseverance has kept me going over the years. Things rarely happen overnight. Filmmakers should be prepared for many years of hard work. The sheer toil can be healthy and exhilarating.

Although for many years I lived hand to mouth — sometimes in semi-poverty — I have lived like a rich man ever since I started making films. Throughout my life I have been able to do what I truly love, which is more valuable than any cash you could throw at me. At a time when friends were establishing themselves by getting university degrees, going into business, building careers and buying houses, I was making films, investing everything back into my work. Money lost, film gained.

Ultimately, this notion of doing what you love is rooted in defining your own success, which often requires the bravery of not buying into the cultural template. Herzog captures this elegantly:

Even if I went broke, I wouldn’t be able to sell anything to the highest bidder. What makes me rich is that I am welcomed almost everywhere. I can show up with my films and am offered hospitality, something you could never achieve with money alone… For years I have struggled harder than you can imagine for true liberty, and today am privileged in the way the boss of a huge corporation never will be.

Observing that happiness and meaningfulness are not necessarily the same thing — something researchers have since confirmed — Herzog echoes artist Agnes Martin’s assertion that doing what you were born to do is the secret of happiness and tells Cronin:

I find the notion of happiness rather strange… It has never been a goal of mine; I just don’t think in those terms.

[…]

I try to give meaning to my existence through my work. That’s a simplified answer, but whether I’m happy or not really doesn’t count for much. I have always enjoyed my work. Maybe “enjoy” isn’t the right word; I love making films, and it means a lot to me that I can work in this profession. I am well aware of the many aspiring filmmakers out there with good ideas who never find a foothold. At the age of fourteen, once I realized filmmaking was an uninvited duty for me, I had no choice but to push on with my projects. Cinema has given me everything, but has also taken everything from me.

(This calls to mind a line Susan Sontag wrote in her diary in March of 1979: “There is a great deal that either has to be given up or be taken away from you if you are going to succeed in writing a body of work.”)

Herzog describes his ideation process in almost violent terms, framing the creative act as an inherently ambivalent one, oscillating between creation, destruction, and purging:

The problem isn’t coming up with ideas, it is how to contain the invasion. My ideas are like uninvited guests. They don’t knock on the door; they climb in through the windows like burglars who show up in the middle of the night and make a racket in the kitchen as they raid the fridge. I don’t sit and ponder which one I should deal with first. The one to be wrestled to the floor before all others is the one coming at me with the most vehemence. I have, over the years, developed methods to deal with the invaders as quickly and efficiently as possible, though the burglars never stop coming. You invite a handful of friends for dinner, but the door bursts open and a hundred people are pushing in. You might manage to get rid of them, but from around the corner another fifty appear almost immediately… Finishing a film is like having a great weight lifted from my shoulders. It’s relief, not necessarily happiness. But you relish dealing with these “burglars.” I am glad to be rid of them after making a film or writing a book. The ideas are uninvited guests, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t welcome.

Channeling T.S. Eliot’s notion of the mystical quality of creativity and Bukowski’s assertion that true creative work “comes unasked out of your heart and your mind and your mouth and your gut,” Herzog — who, like Maira Kalman, sees walking as a creative catalyst — considers how his ideas arise:

My films come to me very much alive, like dreams, without explanation. I never think about what it all means. I think only about telling a story, and however illogical the images, I let them invade me. An idea comes to me, and then, over a period of time — perhaps while driving or walking — this blurred vision becomes clearer in my mind, pulling itself into focus.

[…]

When I write, I sit in front of the computer and pound the keys. I start at the beginning and write fast, leaving out anything that isn’t necessary, aiming at all times for the hard core of the narrative. I can’t write without that urgency. Something is wrong if it takes more than five days to finish a screenplay. A story created this way will always be full of life.

In that creative act, Herzog argues, lies the artist’s broader cultural responsibility to continually reinvent the established forms:

We need images in accordance with our civilization and innermost conditioning, which is why I appreciate any film that searches for novelty, no matter in what direction it moves or what story it tells… The struggle to find unprocessed imagery is never-ending, but it’s our duty to dig like archaeologists and search our violated landscapes. We live in an era when established values are no longer valid, when prodigious discoveries are being made every year, when catastrophes of unbelievable proportions occur weekly. In ancient Greek the word “chaos” means “gaping void” or “yawning emptiness.” The most effective response to the chaos in our lives is the creation of new forms of literature, music, poetry, art and cinema.

And yet being preoccupied with form can be limiting — it should emerge from the story organically rather than seek to shape it:

I don’t consciously reflect on aesthetics before making a film because, for me, the story always dictates such things. Of course, aesthetics do sometimes enter unconsciously through the back door, because whether we like it or not our preferences always somehow influence the decisions we make. If I were to think about my handwriting while writing an important letter, the words would become meaningless. When you write a passionate love letter and focus on making sure your longhand is as beautiful as possible, it isn’t going to be much of a love letter. But if you concentrate on the words and emotions, your particular style of longhand – which has nothing to do with the letter per se — will somehow seep in of its own accord. Aesthetics, if they even exist, are to be discovered only once a film has been completed.

Herzog doesn’t shy away from touching on the existential:

We can never know what truth really is. The best we can do is approximate… Truth can never be definitively captured or described, though the quest to find answers is what gives meaning to our existence.

In one of his most endearingly characteristic proclamations, Herzog tells Cronin why he has never taken vacation:

It would never occur to me… I work steadily and methodically, with great focus. There is never anything frantic about how I do my job; I’m no workaholic. A holiday is a necessity for someone whose work is an unchanged daily routine, but for me everything is constantly fresh and always new. I love what I do, and my life feels like one long vacation.

Above all, however, Herzog reveals himself as a rare master of prioritizing presence over productivity:

I work best under pressure, knee-deep in the mud. It helps me concentrate. The truth is I have never been guided by the kind of strict discipline I see in some people, those who get up at five in the morning and jog for an hour. My priorities are elsewhere. I will rearrange my entire day to have a solid meal with friends.

Theoretical physicist Lawrence Krauss captures Herzog’s singular spirit in the afterword:

The Werner Herzog I have come to know is not the wild man of his press clippings. He is a caring, thoughtful, playful and essentially gentle human being. Possessing a restless mind, with a fertile and creative imagination, he is a man interested in all aspects of the human experience. Self-taught, he is widely read and deeply knowledgeable. I like to think that one of the reasons we enjoy each other’s company is that we both share a deep excitement in the human experience.

Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed is a spectacular read in its hefty 600-page totality, offering a rare glimpse of one of the most ravenously imaginative minds of our time. Complement it with other spectacular interviews with David Foster Wallace, Jeanette Winterson, Leonard Cohen, Seth Godin, Dani Shapiro, William Faulkner, Bob Dylan, Adam Phillips, Pablo Picasso, Malcolm Gladwell, and Susan Sontag.